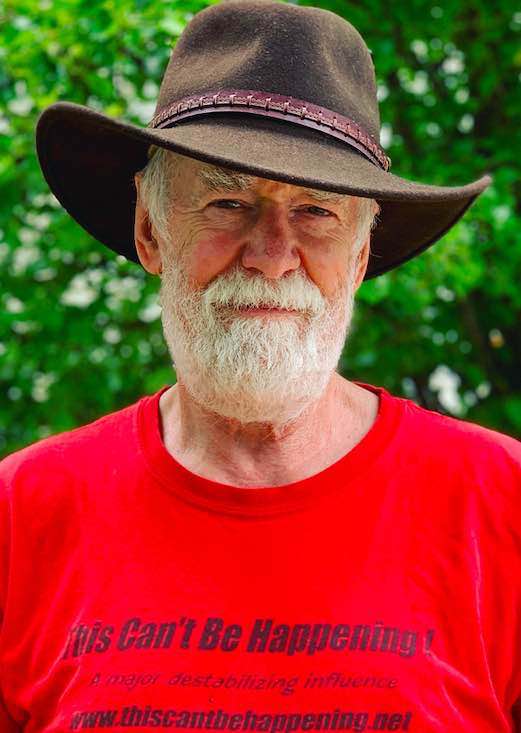

By Dave Lindorff

As someone who has spent nearly three frustrating years actively advocating the impeachment of President George Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney for their many crimes and abuses of power, I have to admit that not only did it not happen, but that the likelihood of their being indicted and brought to trial now that they have left office is exceedingly slim.

While both men are clearly guilty of war crimes, and have in fact admitted to willful violation of international law and the US Criminal Code relating to torture and treatment of captives, and while Bush has admitted to the felony of willfully violating the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), and while a good case of defrauding Congress could be made against both men with regard to their claims made to justify the invasion of Iraq, not to mention a host of other crimes large and small, I think it is clear that the new administration of President Barack Obama does not want to be seen trying to put the president and vice president in the slammer (where they so deserve to be). For better or worse, Obama has decided to pursue a less confrontational politics in Washington.

That said, I would argue that there can be a good case made, both legally and politically, for the convening of a Truth & Reconciliation Commission, which could put all key people in the last administration on the stand and under oath and klieg lights to explain just what they did and why.

Of course, such a commission, if established by an act of Congress, would on one level amount to letting off the hook people whose criminal actions have led to the deaths of over a million people, including over 4500 Americans in uniform, to the torturing of hundreds and perhaps thousands, and to the undermining of the constitutional rights of all the people of this nation. And yet, it may be the best way to establish just what the extent and nature of those crimes were, who was harmed, and how to avoid such reckless and criminal behavior by a president and an administration in the future.

Furthermore, if properly constituted and empowered, such a commission could still lead to prosecutions in the end.

Here’s how it might work: The commission would call administration officers, whether former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld or Vice President Cheney. Under oath, they would be asked what their roles were in, say, the authorization, promotion and covering up of torture. If they answered truthfully, they would be immune from prosecution for any crimes they admitted to, but the world would know for all time what they had done. If they refused to answer, or if they were to lie to the commission, however, they would be subject to possible indictment for contempt or perjury—charges that could place them before a judge or even a grand jury.

Moreover, if lower-ranking members of the administration, called before such a commission, chose the route of coming clean about their role in administration crimes, it would both provide evidence that could later be used to prosecute higher officials who might refuse to appear and testify before such a commission, and at the same time would tend to create a public sentiment in favor of prosecution. A key to the success of such an approach is that the enabling legislation would have to hold out the possibility of prosecution for those who refused to participate, or who lied to the commission.

A truth & reconciliation commission would have to be authorized by an act of Congress, I believe, because only Congress could offer the necessary waiver from prosecution for a capital crime like torture in which victims have died, as is the case with the torture that US military forces and CIA agents have engaged in over the past eight years. But the new Congress should be willing to support such an act, because, far from being retribution, the truth & reconciliation process, which was used in South Africa, and which has been used in other countries recovering from past criminal rule, could be presented as a way of getting out the facts, and of restoring the country’s international reputation, without trying to put anyone behind bars.

Moreover, I think that the vast majority of the American public wants to see some kind of reckoning made with the past eight years of secret government, official lying, and criminal actions by many of the top officials of the land.

If South Africans can respond to generations of a criminal apartheid regime and a police state with a truth & reconciliation process, so can we in America.

It is, after all, the truth, not the punishment of criminals, however heinous, that sets us free.

___________________

DAVE LINDORFF is a Philadelphia-based journalist. His latest book is “The Case for Impeachment” (St. Martin’s Press, 2006 and now available in paperback edition). His work is available at www.thiscantbehappening.net