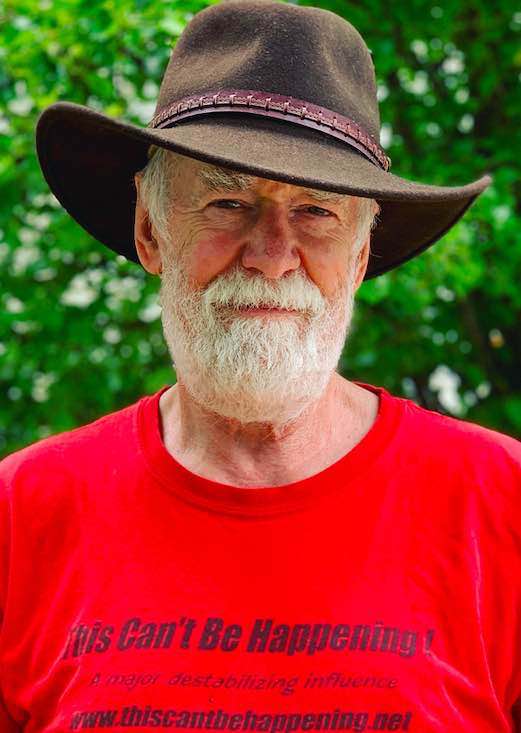

By Dave Lindorff

For the last two weeks, I've been contemplating the mysteries of a post-and-beam barn, trying to work out how to rescue the long-ignored structure from the fate of many barns of its vintage (probably about 150 years old), which is total collapse.

This particular barn was left unattended for years by its last owner, and I am guilty of continuing that neglect for the 12 years that I have owned it. I knew that the shingles on its roof had long passed their sell-by date. When we first bought the property, the shingles had that telltale roughness that announced that they were eroded and brittle. The chronically wet ground floor was also a pretty convincing sign that the roof wasn't doing its job of keeping the rain out. But the real evidence of looming disaster were the plants that began to sprout right out of the roof this wet summer. Big plants. Even a few young trees. And the mushrooms growing out of the ends of exposed beams. Not a good sign.

I made my way gingerly up the rickety stairs to the second floor in August, and looked around at the underside of the roof. Someone had obviously once re-roofed the structure perhaps two decades ago or more, using plywood sheathing over the old slats, but the plywood from the front wall on up halfway to the ridge was all rotten. One corner of the roof had actually fallen in, so there was an eight-foot-by-four-foot unimpeded view of the sky. Several rafters were so rotten they had cracked and were sagging downward, held up only by the rusty nails coming down into them from the gimpy plywood and slats above them.

I've never attempted anything this big, but I decided I simply had to rescue this sad old building. Someone had once put an enormous effort into its hand-hewn ten-inch-by-ten-inch beams (probably chestnut), notched and pinned together by wooden pegs. There had probably been a community barn-raising to erect the thing, once upon a time.

There's no community today to do this kind of work, unless you're part of one of the Amish communities in central Pennsylvania or Ohio. I have a few friends I could probably get to hold a ladder, or maybe help me hoist some shingles to the roof, once I get to that point, but nobody would likely want to devote a week or two to the hard labor of rebuilding a dangerous old barn, just for the sake of community spirit or camaraderie. Those days are gone. People are just too busy trying to get by.

So I'm doing this project myself.

I started from the ground up, using a hydraulic house jack to lift giant floor joists whose tenons had rotted away, and installing heavy uprights posts made of treated lumber, to fend off the inevitable carpenter ants that are attracted to damp wood like bees to clover. Then I moved to the second floor, and began replacing the planking that had rotted away to the point that it could no longer hold a child's weight. (It didn't help things that the last owner of the property had let a flock of chickens inhabit the second floor, and that, until I had cleaned it out, it was four or five inches deep in desiccated chicken sh*t.) Once I had a sound second floor, so I could walk around freely without having to test each board before stepping on it, it was time to tackle the roof.

That's when I first noticed that the front of the barn was actually tilting forward, as if poised to take a dive.

Uh-oh.

This was an urgent fix. I raced out to Deck's, an old family-owned hardware store in the next town├ éČ"a throwback to an earlier time, with floor-to-ceiling cabinets that had the items inside mounted on the doors, so you could see what you were looking for, instead of having to struggle to explain to the shop personnel the shape of some item, the name of which you could never, in a million years, recall, if indeed you had ever known it. In my case, it was a humongous turnbuckle├ éČ"a device with welded eyes at either end on threaded bolts, one reverse-threaded. By attaching this turnbuckle to an eye-bolt that was put through the sill beam and clamped down with a nut and a large washer on the outside, and attaching one end of a big cable to the other, with the cable stretching to another eyebolt running through the opposite sill beam, I could crank the thing around and shorten the cable, pulling the barn together, I figured.

When I got back to my barn and assembled this apparatus, drilling the holes through the two sill beams, and began the cranking process, I could see immediately that the tilted upper story was pulling back, but then it dawned on me: How did I know I wasn't also pulling the other ood wall over with the bad one? I checked it out with a level, and it was still nice and vertical, but obviously I couldn't count on its staying that way. I needed to put in some angle braces against the opposite sill to keep it from moving.

But there was still something I hadn't anticipated. I kept cranking in the outer wall, and managed to mover its top about four inches back towards true. It was still leaning out about four inches though, and the cable was getting disturbingly taut. Then I noticed that the eyes of the huge eyebolts I had put through the sill beams were starting to pull away from their nice round shape!

Damn! I should have found bolts with welded eyes, or taken these to be welded.

I couldn't bring myself to re-loosen the cable, so I gave the turnbuckle a couple more careful cranks, checked the eyes, and then decided that was as far as I could go.

Later, I was talking with a contractor who does renovations of old houses about the problem, and, after first declaring me ├ éČ┼"crazy├ éČ Ł for attempting a project of this scale on my own, he explained that unbeknownst to me, when I was cranking the wall back, I was also trying to lift the entire roof of the barn with that turnbuckle. It was actually the slumping and spreading of the heavy roof's angled rafters that was forcing the front wall out. In trying to pull it back, I was actually trying to force the roof back up to its original angle.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).