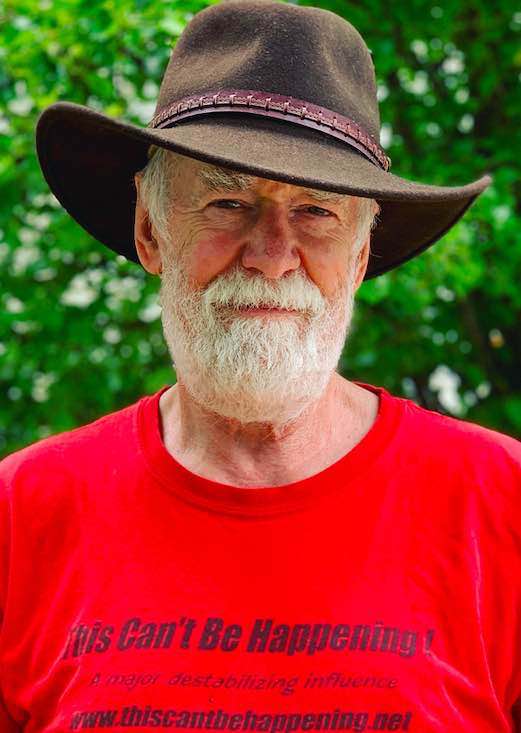

By Dave Lindorff

If the day comes that Congress finally does its duty and begins an

impeachment effort against 9th Circuit Federal Appeals Judge Jay Bybee,

the former Bush assistant attorney general who in 2002 authored a key

memo justifying the use of torture against captives in the Afghanistan

invasion and the so-called “War on Terror,” it would be fitting

punishment to watch him squirm as his own words as a judge were played

back to him.

It was as an Appeals Court Judge Bybee, sitting on a case being

heard in 2006 by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, that he wrote the

following words:

“The only thing we have to enforce our judgements is the power

of our words. When these words lose their ordinary meaning—when they

become so elastic that they may mean the opposite of what they appear

to mean—we cede our own right to be taken seriously.” (Amalgamated

Transit Union Local 1309 v. Laidlaw Transit Services, Inc.).

Yet causing words to become “so elastic that they may mean the

opposite of what they appear to mean” was precisely the goal of the

48-page memo, just released by the Obama Administration, which Bybee

wrote for the Bush/Cheney White House authorizing the use of what any

ordinary person, and indeed the US Criminal Code, would define as

torture against captives held in Bagram, Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo and

elsewhere.

The actual Geneva Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel,

Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, incorporated in 1996 by

act of Congress as a part of the US Criminal Code, Title 18, Sections

2340-2340A, is quite unambiguous in its proscription. As Bybee notes in

his memo, the Convention Against Torture defines torture as:

“…any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or

mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as

obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession,

punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is

suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a

third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind,

when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or

with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person

acting in an official capacity."

Now we know that what US CIA agents, military interrogators, and

even prison guards charged with “softening up” detainees, were doing to

captives included repeated waterboardings (over 100 times in the case

of some captives), slamming into walls while leashed to a neck

restraint, enforced sleeplessness for as long as 11 days at a time,

subjection to prolonged periods of extreme heat or cold, attacks by

dogs, being locked in a box with biting insects, etc. ad nauseum.

Yet Bybee, in his capacity as counsel to the president in the

office of the Attorney General, went to great creative lengths to make

the words in that act “elastic” to the point that they “lose their

ordinary meaning.”

For example, in his memo Bybee wrote:

“We…conclude that certain acts may be cruel, inhumane or

degrading, but still not produce pain and suffering of the requisite

intensity to fall within Sec. 2340A’s proscription against torture.”

Then, because he saw that that term “severe” in the statute was

problematic, Bybee went out of his way to try to make it mean something

more extreme. He found a legal case involving a hospital that was being

sued for refusing to admit an emergency medical patient, concluding

that severe pain would have to be pain “equivalent to (sic) intensity

to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ

failure, impairment of bodily function or even death.”

Obviously, when someone says they have a “severe headache” or tells

the doctor that they have a “severe pain” in their lower back, they

aren’t talking about facing death, organ failure of impairment of

bodily function. They are using the word in its “ordinary meaning” to

communicate that they are hurting badly. But then Asst. Attorney

General Bybee isn’t interested in what Judge Bybee called “the ordinary

meaning” of words. He’s looking for weasel words. He’s trying to get

words to be “elastic,” and to mean “the opposite of what they appear to

mean.”

But Bybee also recognized in the event that Bush or his

subordinates were someday to be hauled before a court and prosecuted

for war crimes, he would need to offer them a second line of defense,

so, ever the good mob attorney, the future appellate court judge

offered up this beauty:

“To violate Section 2340A, the statute requires that severe

pain and suffering must be inflicted with specific intent. In order for

a defendant to have acted with specific intent, he must expressly

intend to achieve the forbidden act.”

What this means, writes Bybee, is that, “If the defendant [the

government torturer] acted knowing that severe pain or suffering was

reasonably likely to result from his actions, but no more, he would

have acted with only general intent” but not “specific intent” to cause

pain.” Put another way, he writes, “As a theoretical matter therefore,

knowledge alone that a particular result is certain to occur does not

constitute specific intent.”

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).