This piece was reprinted by OpEdNews with permission or license. It may not be reproduced in any form without permission or license from the source.

Source: Consortium NewsFifty years ago, exactly one month after John Kennedy was killed, the Washington Post published an op-ed titled "Limit CIA Role to Intelligence." The first sentence of that op-ed on Dec. 22, 1963, read, "I think it has become necessary to take another look at the purpose and operations of our Central Intelligence Agency."

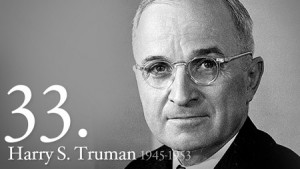

It sounded like the intro to a bleat from some liberal professor or journalist. Not so. The writer was former President Harry S. Truman, who spearheaded the establishment of the CIA 66 years ago, right after World War II, to better coordinate U.S. intelligence gathering. But the spy agency had lurched off in what Truman thought were troubling directions.

Sadly, those concerns that Truman expressed in that op-ed -- that he had inadvertently helped create a Frankenstein monster -- are as valid today as they were 50 years ago, if not more so.

Truman began his article by underscoring "the original reason why I thought it necessary to organize this Agency ... and what I expected it to do." It would be "charged with the collection of all in telligence reports from every available source, and to have those reports reach me as President ... without Department ' treatment' or interpretations."

Truman then moved quickly to one of the main things bothering him. He wrote "the most important thing was to guard against the chance of intelligence being used to influence or to lead the President into unwise decisions."

It was not difficult to see this as a reference to how one of the agency's early directors, Allen Dulles, tried to trick President Kennedy into sending U.S. forces to rescue the group of invaders who had landed on the beach at the Bay of Pigs, Cuba, in April 1961 with no chance of success, absent the speedy commitment of U.S. air and ground support.

Wallowing in the Bay of Pigs

Arch-Establishment figure Allen Dulles had been offended when young President Kennedy had the temerity to ask questions about CIA plans before the Bay of Pigs debacle, which had been set in motion under President Dwight Eisenhower. When Kennedy made it clear he would NOT approve the use of U.S. combat forces, Dulles set out, with supreme confidence, to mousetrap the President.

Coffee-stained notes handwritten by Allen Dulles were discovered after his death and reported by historian Lucien S. Vandenbroucke. They show how Dulles drew Kennedy into a plan that was virtually certain to require the use of U.S. combat forces. In his notes, Dulles explained that, "when the chips were down," Kennedy would be forced by "the realities of the situation" to give whatever military support was necessary "rather than permit the enterprise to fail."

The "enterprise" which Dulles said could not fail was, of course, the overthrow of Fidel Castro. After mounting several failed operations to assassinate him, this time Dulles meant to get his man, with little or no attention to how the Russians might react. The reckless Joint Chiefs of Staff, whom then-Deputy Secretary of State George Ball later described as a "sewer of deceit," relished any chance to confront the Soviet Union and give it, at least, a black eye.

But Kennedy stuck to his guns, so to speak. He fired Dulles and his co-conspirators a few months after the abortive invasion, and told a friend that he wanted to "splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it into the winds." The outrage was very obviously mutual.

When Kennedy himself was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, it must have occurred to Truman -- as it did to many others -- that the disgraced Dulles and his unrepentant associates might not be above conspiring to get rid of a president they felt was soft on Communism and get even for their Bay of Pigs fiasco.

"Cloak and Dagger"

While Truman saw CIA's attempted mousetrapping of President Kennedy as a particular outrage, his more general complaint is seen in his broader lament that the CIA had become "so removed from its intended role ... I never had any thought that when I set up the CIA that it would be injected into peacetime cloak and dagger operations. ... It has become an operational and at times a policy-making arm of the government." Not only shaping policy through its control of intelligence, but also "cloak and dagger" operations, presumably including assassinations.

Truman concluded the op-ed with an admonition that was as clear as the syntax was clumsy: "I would like to see the CIA restored to its original assignment as the intelligence arm of the President, and that whatever else it can properly perform in that special field -- and that its operational duties be terminated or properly used elsewhere." The importance and prescient nature of that admonition are even clearer today, a half-century later.

But Truman's warning fell mostly on deaf ears, at least within Establishment circles. The Washington Post published the op-ed in its early edition on Dec. 22, 1963, but immediately excised it from later editions. Other media ignored it. The long hand of the CIA?

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).