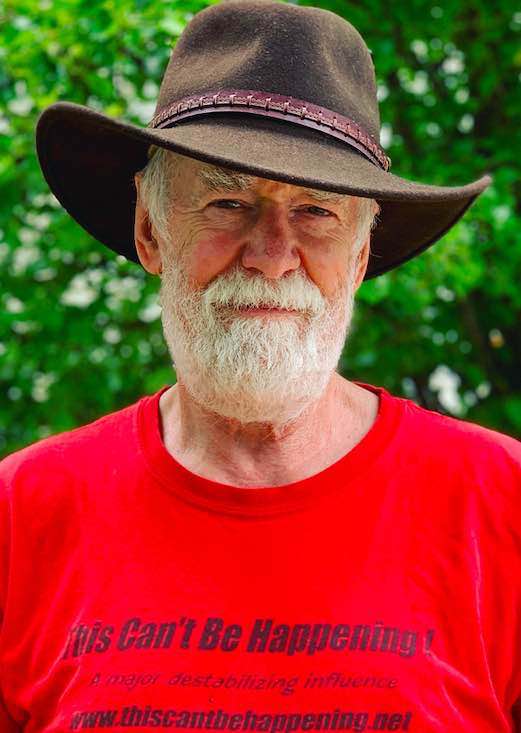

By Dave Lindorff

Listening to the endless stream of cars passing my house every day,

and knowing, from watching them from my mailbox, that they are almost

all carrying just one person, either commuting to work or running some

kind of errand, I know we are headed for disaster.

Two days ago, there was a report by Agence France Presse

about the ongoing destruction of the world’s remaining wetlands (60

percent have already been destroyed by man over the past century), and

how they contain within them an amount of stored carbon equal to all

the carbon currently in the atmosphere. Global warming and property

development are drying out those remaining wetlands, causing the

release of that carbon, which will more than negate even the most

radical efforts at reducing carbon emissions from power plants,

factories and automobiles.

There are also credible, well-researched reports

that even a few more degrees of temperature rise in the arctic regions

of Siberia and northern North America will melt the permafrost and

release as much 400 gigatons of methane gas trapped in frozen

clathrates for millennia—the release of which would cause global

temperatures to soar to levels not seen in 250 million years (methane

is 20 times as potent a global warming gas as CO2). Vast regions of

Siberia are already bubbling with releasing methane as the permafrost

line moves north.

Now I grant that our corporate media, ever focused laser-like on

important stories like Brittany Spears’ return to the stage and on the

latest gaffe of one or the other presidential candidate, have not been

very interested in alerting the masses to these disasters now in

progress that could end humanity’s run on the planet (along with

exterminating most of the rest of the life on the planet too). But that

said, at this point everyone has surely heard enough, and witnessed

enough in person of the dramatic changes taking place in the earth’s

climate, to know that something scary is going on.

And yet, people are not just going about their business as

usual—they are actually, for the most part, complaining not about the

lack of highly energy-efficient transportation, the lack of alternative

and less energy-wasting public transit, and the lack of government

funding for a crash program into researching carbon-free energy

solutions, but rather about the high price for carbon fuels. People are

clamoring for solutions to make gasoline cheaper!

Years ago, back in the 1970s during an Arab-led oil embargo, when

gas prices soared, there were mass campaigns to organize car pools. No

such campaigns are being organized today, and if any are they don’t get

any media attention. Instead we read that geologists are saying that

massive quantities of untapped oil reserves exist in the far north.

Now the last thing we should be wanting to do is take that nicely

sequestered carbon out of the ground and burn it into CO2! But that’s

what many Americans want done. Screw the climate! We want our cheap gas!

There are so many things we could be doing right now to reduce

carbon emissions—as individuals and as a nation. Turning off

air-conditioners would be one. Why should entire houses be cooled by

central air? Cool one room and use it for the hottest part of the day

if need be. Live downstairs during the hottest months and close off the

upstairs when it gets too hot. Ditto in the winter. There’s no need to

occupy and heat an entire house when it gets really cold. Most

Americans’ homes are way too large anyhow, but if you need that much

room, use it when it doesn’t require all that extra energy to heat and

cool. (When I lived in Cambridge, England as a kid, we used to sleep in

unheated bedrooms under cozy comforters, and then in the morning, I’d

go down and light a fire in the living room where we’d be during the

day. It would be cold as hell until the fire started, but not for

long.) Share rides. Plan errands so that many things get taken care of

on one outing, instead of in multiple run-outs. Use bicycles. I have

yet to see, on my own bike rides in town or when driving anywhere,

someone who is actually riding a bike on some errand—carrying a load in

a basket or in a backpack. The only bikers I see are people dressed

like Tour de France racers out for some exercise. What’s the matter

with using bikes for a purpose, instead of the family car?

I’m not trying to criticize, or to say I’m more ecologically

virtuous. I’m looking at this as an unprecedented disaster that is

dooming my kids, or their future children, to a life of strife, misery

and maybe even catastrophe. If I don’t take serious action—and I don’t

just mean individual life changes, but political action—to try and save

their world, I am guilty of a serious crime. And so are we all.

What the hell happened to any sense of shared responsibility, not just for society, but for our own offspring?

Most decent parents are ready to sacrifice in their lifestyles in

order to send their kids to college, or to help them out financially

when they are starting out as young adults. But for some strange reason

nobody seems ready to sacrifice at all when it comes to rescuing their

collective future. This makes no sense.

And yet, this is what our mass culture has done to us. As a nation,

as a people, we cannot think beyond our own noses. We cannot even think

about the need to act in our own and our children’s interest.

Seventeen years ago, I had occasion while living in Shanghai,

China, to visit a rural area in Anhui Province that the year before had

been devastated by a flood so huge that the entire region had been not

just flooded, but put deep underwater. As I neared a county seat town

that was my intended destination, the bus I was on passed a

dike-building project. Thousands of peasants were laboring by hand,

with shovels and wheelbarrows, to erect a 50-foot wall of earth to keep

the river in its banks in the event of another such flood. I got off

the bus and, with my travel companion, started walking towards the

project. When we were spotted, thousands of those workers dropped their

shovels and ran towards us. It was a terrifying moment to have so many

people heading towards and surrounding us, but they were very

friendly—just curious because none of them had ever met a westerner. We

began talking with them, and learned that they were all peasants who

had left their fields to build this colossal new Great Wall of dirt.

They brought us to the worksite and showed us how they would bring

their wheelbarrows to the base of the dike, and then attach a cable,

which was connected to a winch operated by those ubiquitous

one-cylinder, two-stroke kerosene tractors used across rural China. The

winch would whip the barrow up the steep hillside, with a peasant

running up behind keeping it upright. At the last minute, the peasant

would flip the barrow, dumping the dirt and releasing the hook. Then

he’d be off down the hill to collect more dirt.

What struck me, besides their ingenuity, was how all these

thousands of people had left their own fields to labor for the

collective good that year.

I tried at the time to contemplate my fellow Americans doing the same thing, and couldn’t for the life of me imagine it.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).