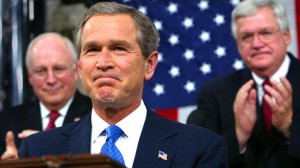

President George W. Bush receiving applause during his 2003 State of the Union Address in which he laid out a fraudulent case for invading Iraq.

In the early 1980s, when it became clear to me that the Reagan administration was determined to lie incessantly about its foreign policy initiatives -- that it saw propagandizing the American people as a key part of its success -- I pondered this question: What is the proper role of a U.S. journalist when the government lies not just once in a while but nearly all the time?

Should you put yourself into a permanently adversarial posture of intense skepticism, as you might in dealing with a disreputable source who had lost your confidence? That is, assume what you're hearing is unreliable unless it can be proven otherwise.

But it wasn't that easy. At the time, I was working as an investigative reporter for The Associated Press in Washington and many of my senior news executives were deeply sympathetic to Reagan's muscular foreign policy after the perceived humiliations of the lost Vietnam War and the long Iranian hostage crisis.

General manager Keith Fuller, the AP's most senior executive, saw Reagan's Inauguration and the simultaneous release of the 52 U.S. hostages in Iran on Jan. 20, 1981, as a national turning point in which Reagan had revived the American spirit. Fuller and other top executives were fully on-board Reagan's foreign policy bandwagon, so you can understand why they wouldn't welcome some nagging skepticism from a lowly reporter.

The template at the AP, as with other major news organizations including the New York Times under neocon executive editor Abe Rosenthal, was to treat Reagan and his administration's pronouncements with great respect and to question them only when the evidence was incontrovertible, which it almost never is in such cases.

So, in the real world, what to do? Though some people cling to the myth that American reporters are warriors for the truth and that tough editors stand behind you, the reality is very different. It is a corporate world where pleasing the boss and staying safely inside the herd are the best ways to keep your job and gain "respect" from your colleagues.

Punishing the Truth

That lesson was driven home during the early 1980s. Some of us actually tried to do our jobs honestly, exposing crimes of state in Central America and elsewhere. Almost universally, we were punished by our editors and marginalized by our colleagues.

Early on, Raymond Bonner at the New York Times wrote courageously about right-wing "death squads" in El Salvador, even as Reagan and his team were disputing those bloody facts on the ground and coordinating with right-wing media attack groups in Washington to put Bonner on the defensive. Amid the smears, Rosenthal pulled Bonner out of Central America, reassigned him to a desk job in New York and caused Bonner to leave the Times.

Even those of us who had some success in exposing major scandals emerging from the brutality in Central America were treated as outsiders whose careers were always fragile. We had to dodge withering fire from the Reagan administration and its right-wing cohorts while keeping one eye on the nervous or angry editors to our backs.

There was really no way to win, no way to pick through all the minefields surrounding the most sensitive stories. If you pressed forward into the ugly scandals -- like the Reagan administration's protection of Nicaraguan Contra drug traffickers or the secret arms deals with Iran and Iraq -- you would surely be "controversialized," a phrase favored by Reagan's "public diplomacy" operatives.

Eventually, one or more of your news executives, sympathetic to Reagan's tough-guy foreign policy, would conclude that you were more trouble than you were worth and you would find yourself out of a job. Next, you could count on most of your colleagues who had protected their own careers by playing it safe to turn on you.

Sometimes even the Left media would join the mob mentality. One of my most disturbing moments came in 1993 when I wrote an article for The Nation pointing out logical inconsistencies in a House Task Force report "debunking" the so-called October Surprise case, whether Ronald Reagan's 1980 campaign went behind President Jimmy Carter's back to block the pre-election release of those hostages in Iran.

I had noted, for instance, that one of the Task Force's key arguments was that because someone had written down William Casey's home phone number on a certain date that Casey must have been at home and thus couldn't have been where some witnesses had placed him. But that "home phone number" alibi made no logical sense, nor did some of the other illogical conclusions in the Task Force's final report.

My Nation article prompted an angry letter from the Task Force chief counsel Lawrence Barcella who responded with a mostly ad hominem attack on me. After the letter arrived, I received a call from a senior Nation editor who told me I would be given a small space to respond but that I should know that "we agree with Barcella."

Building a Home

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).