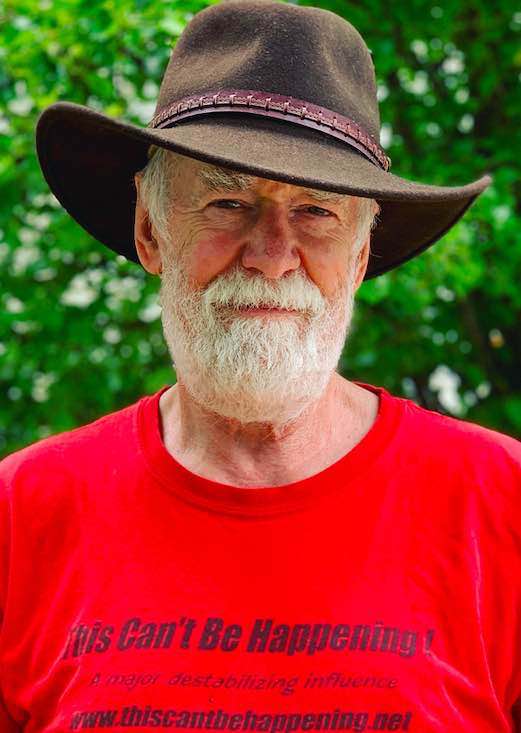

By Dave Lindorff

The new book Murdered by Mumia, by Maureen Faulkner and right-wing Philadelphia radio talkshow shock jock and Bill O'Reilly wannabe Michael Smerconish, due out this Thursday, got top billing in the feature section of the Philadelphia Inquirer on Sunday with an excerpt headlined “A Widow Speaks,” which implied that the wife of slain Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner was finally breaking her silence. In fact, Faulkner has been quite vocal for a quarter of a century in her tireless campaign, backed by the Fraternal Order of Police, to have Abu-Jamal, who was found guilty of murdering her husband, executed.

She has persisted in this campaign, of which this book written with the help of equally avid death penalty booster Smerconish is a kind of culmination, despite reams of evidence that Abu-Jamal never got a fair trial, despite the fact that the prosecution hid evidence of possible innocence and that the police or the prosecutor coerced false testimony from key witnesses. They have persisted in that campaign despite a 2003 study by a state supreme court-appointed committee confirming that the entire Philadelphia legal system and the Pennsylvania appellate courts that review that system are rife with racism, and that death penalty prosecutions, especially in Philadelphia, are poisoned by prejudice.

In the Inquirer's excerpt of her forthcoming book, Faulkner says that she wants Abu-Jamal—whose death sentence, by the way, was overturned by a federal district judge in December 2001 on grounds that the judge’s instructions to the jury, and the form for polling the jury in the penalty phase were confusing and predisposed the jury towards death—killed because she doesn’t trust that the alternative—life without possibility of parole—means what it says. In her view the only way to keep Abu-Jamal from walking the streets a free man, which to her is anathema, is to put him six feet under.

That’s surely a bitter pill to swallow for someone who lost her husband, but it doesn’t make it any less true.

Just take a couple of issues by way of example.

When prosecutor Joseph McGill made his summation to the jury in this case, he came to the witness Robert Chobert, a taxi cab driver who claimed his vehicle had been parked directly behind Faulkner’s squad car, in front of and to the right of which Faulkner’s shooting is supposed to have taken place. No other witness saw that taxi there, and even the other key eyewitness to the shooting, a black prostitute named Cynthia White, in drawings that she made for the police, did not include the taxi, although she did draw the Volkswagen owned by Abu-Jamal’s brother William, which was parked in front of Faulkner’s squad car and a Ford sedan that was parked in front of the VW and that, together with its anonymous owner, had absolutely nothing to do with the incident. McGill told the jury that of all four of the eyewitnesses to parts of the shooting, they should certainly believe the white male Chobert. After all, he asked them, “What motivation would Robert Chobert have to make up a story 35 to 45 minutes later?”

Well, in fact, Chobert, if he thought it could get him out of a serious legal pickle—driving a cab on a suspended license for DUI--had ample reason to lie. But McGill, in a clear case of prosecutorial misconduct, had never notified the court and the defense, as required by law, much less the jury, that Chobert, who was illegally driving his cab while his chauffeur's license was under suspension for a DUI conviction, had asked him if he could “fix” his problem. While McGill never did fix it, and may never have suggested he would, the jury—and the defense and the judge! --surely should have known, in evaluating the truthfulness of Chobert’s testimony, that he at least was thinking the prosecutor was in a position to help him if he testified favorably. The jury, which never even learned about the suspended license, which in itself would have gone to the issue of the witness’s truthfulness, was also not told, because the judge ruled it immaterial, that Chobert at the time of his testimony and at the time of the shootings (remember there were two people shot that night: Faulkner and Abu-Jamal), was serving five-year’s probation for felony arson-for-pay following conviction for fire-bombing an elementary school. As Chobert no doubt knew at the time he found himself talking to police the night of the shooting, his driving a cab on a suspended license alone could have been treated as a violation of probation that could have sent him to jail! The jury never knew this.

The issue of trial Judge Albert Sabo’s statement of racial bias and intent to throw the trial was brought before another common pleas judge, Patricia Dembe, in 2001. She, rather incredibly, refused to see any problem, saying that even if Sabo, by then deceased, had been racist (she ignored the matter of his stated intent to “fry” the defendant, focusing only on the racial epithet), it wouldn’t matter, since “juries decide” guilt or innocence. But Sabo’s role and his racist predilection for guilt and death sentence were much more crucial when he became ultimate arbiter of fact in the 1995 Post-Conviction Relief Act hearing. There, the matter of Chobert’s DUI conviction and lifted driving privileges, as well as his effort to get things “fixed,” were brought to light. Sabo, however, simply ruled that this important evidence, improperly withheld by the prosecutor at the trial, was of no consequence.

Sabo would do this over and over at that PCRA, retroactively sanctioning every error, excess and abuse by both the prosecution and himself, and undermining every attempt by the defense to bring in new witnesses or to further question old witnesses. (That hearing was so biased that both the Inquirer and the Daily News in Philadelphia, hardly advocates of Abu-Jamal, called for Sabo's removal from the proceedings.) Judge Dembe never bothered to examine the role that Sabo’s obvious bias and racism would play on Abu-Jamal’s appeal, but the damage was potentially fatal.

Because of a law pushed through Congress that very year in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing, federal courts were told they had to give primacy to factual decisions by state courts, and could only overturn those “facts” if a state judge or court was found to have made an “unreasonable” error, not just an error. (The Pennsylvania Supreme Court whjich later upheld Dembe's pinched view of the importance of judicial impartiality included five judges who had received the endorsement of the Fraternal Order of Police, and one judge who had earlier been a Philadelphia DA fighting Abu-Jamal's appeal. None recused themselves.)

In his decision rejecting all 20 of Abu-Jamal’s claims of constitutional error in his trial, Federal District Judge William Yohn repeatedly established that Sabo had erred, but then he would add that he could not say the error in question was “unreasonable” as demanded by the 1996 Effective Death Penalty Act. So when Judge Dembe wrote, in her decision, “as long as the presiding judge’s rulings were legally correct, claims as to what might have motivated or animated those rulings are not relevant,” she was ignoring the fact that the primary person determining the correctness of those rulings, 13 years later, was that same Judge Sabo. If that is not “Through the Looking Glass” courtroom logic, I don’t know what is.

This is not the place to go through a list of everything that was wrong with Abu-Jamal’s trial and appeals process. I wrote a critically acclaimed book on that topic (Killing Time, Common Courage Press, 2003). It is 345 pages long, which is about the length that is required to do justice to that list. As well, there is new information out there, in the form of new and recanted witnesses, and newly discovered crime scene photos, that all raise further questions about the integrity of police and prosecution evidence and about the honesty of police witnesses, as well as about the prosecution’s account of how the shootings of Abu-Jamal and Faulkner actually happened. (For example, photos of the spot where Faulkner lay as he was fatally shot in the forehead, taken minutes after the incident, show no evidence of craters or divots where three other high-velocity bullets should have hit, if the shooter, allegedly standing astride the prone officer, had fired down at him and missed, as testified by both Chobert and White. Nor do they show Chobert’s cab. They also show officers casually handling evidence, like the two guns, with no effort to preserve fingerprints, and moving other crime scene evidence, like Faulkner’s hat, the location of which was testified to at the trial.)

The point here is that an angry and grieving widow’s and a publicity-seeking radio personality’s crusade of death aside, we are all diminished when justice is so willingly cast aside in the wrongheaded name of vengeance, as has clearly happened in the case of Mumia Abu-Jamal. No amount of sympathy for Faulkner’s widow should be permitted to sway society or the courts from a commitment to justice, and there has been no justice in this case.

Faulkner is entitled to her anger and her grief, and even to her single-minded obsession with killing a man she’s convinced is her husband’s killer. Smerconish is entitled to his publicity seeking. The scandal is that hundreds of thousands of Philadelphians, white, black and brown, in whose name our legal system operates, have not risen up to demand a new trial in this appalling case. One can only hope that three judges of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, who last spring heard three arguments for reopening or retrying his case, will at last give Abu-Jamal that chance.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).