Is not the Pashtun amenable to love and reason? He will go with you to hell if you can win his heart, but you cannot force him even to go to heaven - Badshah Khan

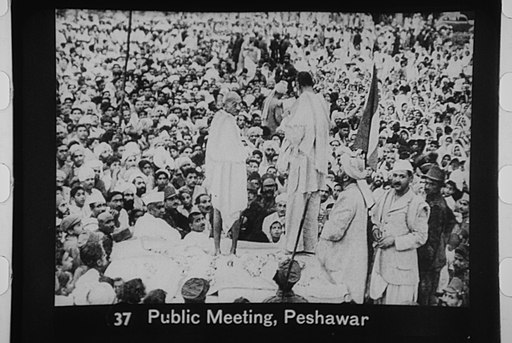

If anyone today could name an historical figure connected to the origin of non-violent resistance against political oppression, it would most likely be India's Mohandas Gandhi. Gandhi virtually defined the idea of non-violent resistance in his struggle to free India from British colonial rule. But in 1929, a Pashtun tribal leader in nearby Afghanistan named Bhadshah Khan - a peer of Gandhi - became an important ally by inaugurating Afghanistan's indigenous non-violent movement known as the Khudai-Khidmatgar - the servants of God. Since Khan realized that God needed no service he decided that by serving God they would in fact be serving humanity and set out to remove violence from their ancient Pashtun tribal code. Known as Pashtunwali, Afghans had lived by the code's elaborate rules for millennia and continue to order their lives by it to this day.

In addition to establishing a leadership council accepted by the community, Pashtunwali laid out in detail the proper behavior for hospitality as well as what was necessary to create security for all including how and when the act of revenge was acceptable.

Following Britain's colonization of Afghan tribal lands east of the Hindu Kush Mountains in 1848, these principles of Pashtun law were gradually replaced by a new British colonial order. Pashtun society was already known to be in need of social reform for its long-standing acceptance of revenge killing. But the British creation of a small, elite landlord class to control and administer the province turned revenge killing into a permanent blood bath.

According to Dr. Sruti Bala of the University of Amsterdam: "With traditional tribal authority diminished, this ruling elite gradually emerged as a group of powerful landlords who fought among each other and increased rivalry among the clans. By introducing their own manner of punishment and control, including fines, levies and even imprisonment, they created a new culture of conflict with its own rules of settlement."

According to Bala "this was a major change in comparison with the tribal councils' traditional focus on limiting conflicts and blame, and resolving feuds without punishment." The 1872 Frontier Crimes Regulation Act further worsened the situation by sanctioning punishments and mass arrests without trial and legal support and placed heavy restrictions on the free assembly of ethnic Pashtuns. The Frontier Crimes Regulations were far stricter in the Pashtun territories than in any other part of British India and directly limited civil liberties. According to Bala, "The infringements on civil as well as basic human rights were legitimized by the apparent need to control the Western frontier as a defensive line against Russian aggression and military advances in the region." And this was of course long before the threat of Soviet communism ever existed.

British competition with Russia for control of Central Asia was a central feature of the 19th-century imperialism known as the Great Game. Over time a delicate balance was reached and Afghanistan used as a buffer state between empires but not without a brutal suppression of the Pashtun tribes by the British.

Khan's appeal to non-violence was accepted by many Pashtuns as a way to resolve deep-rooted social problems while undermining British authority at the same time. Although organized like an army, his recruits swore an oath to renounce violence and to never so much as touch a weapon. Over time, the Khudai-Khidmatgar movement developed an educational network to address the social and cultural reforms needed to leave revenge and retribution behind and move towards non-violent development.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).