This essay is adapted from Seeking Truth in a Country of Lies.

"He wears a mask and his face grows to fit it."

- George Orwell, "Shooting an Elephant"

The lobby of the temple of time travel called the Triplex Cinema in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, was suffused with a nostalgic vibe tinged with the whiff of encroaching death when I walked in for The Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story. I had earlier asked the ticket girl if most of the tickets for the two sold-out preview shows were being purchased by old people; she told me no, that many younger people had also bought tickets. However, I didn't see any.

All I saw were grey or white heads and beards, not with "Time Out of Mind," as Dylan titled his 1997 album, but with time on their minds, as they shuffled into the dark to see where their time had gone and perhaps, if they were not mystified by their fetishistic worship of Dylan, to meditate on who they had become and where they and he were heading in the days to come. I imagined most were aware that Dylan had said that he's been singing about death since he was twelve, and that his music is haunted by images of love and time lost as bells toll for those traveling the road of life in search of forgiveness for their transgressions.

How, I wondered, would this Dylan documentary "story" fashioned by Martin Scorsese, whose own work is marked by themes of guilt and redemption, affect an audience that might never have taken the roads less traveled of their youthful dreams but "fell" into the conformist and oppressive American neo-liberal way of life? Would this film, in Dylan's words, get the audience wondering "if I ever became what you wanted me to be/Did I miss the mark or overstep the line/That only you could see?"

Would nostalgia for their youth be a liberating or mystifying force, now that forty plus years have transformed American society into a conservative, postmodern, shopper's paradise where commodity capitalism has reified all aspects of life, including art objects and artists such a Dylan, imbuing them with magical powers to redeem those who buy their products, which include songs and celebrity "auras"?

I assumed many of those around me had fetishized Barack Obama as a savior even while he was waging endless wars and killing American citizens, bailing out his Wall St. and bank supporters, and jailing more whistleblowers than any American president in history. I knew that Dylan had accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom from this icon of rectitude, who had served to quell all thoughts of rebellion and whose war victims were not counted by those who bought his brand since God was on his side. Here in this darkened dream factory in a hyper-gentrified "liberal" town, my mind was knotted with thoughts and questions that perhaps the film would address.

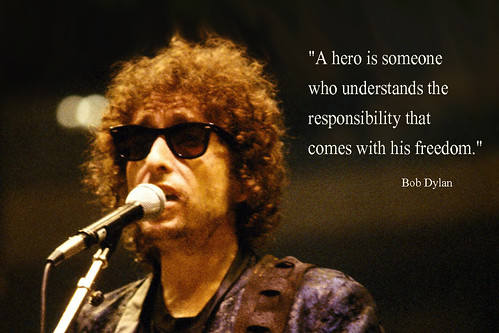

The Man Who Isn't

I knew that no one would answer my questions, but I asked myself anyway. Moreover, I knew there is no Bob Dylan. He is a figment of the imagination - first his own and then the public's. Perhaps behind the character Bob Dylan there is a genuine actor, and I hoped to catch an unintended glimpse of him in the film, but I knew if he appeared it would be obliquely and through a gradual dazzling of truth, as Emily Dickinson would say. An unconscious disclosure. For if the real Bob Dylan took off his mask and stood up, his ardent fans would receive it as a slap in the face, and their illusions would transmogrify into delusions as the spell would be broken. To tell the truth directly is a dangerous undertaking in a country of lies.

Dylan, the spellbinder, has, through his public personae, hypnotized his followers with his tantalizing and wonderful music. "Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me," wrote D.H. Lawrence in his poem, "Song of a Man Who Has Come Through." This sounds like Dylan's artistic credo. His masks (personae = to sound through) have served as his medium of exchange. He has been faithful to his tutelary spirit (if not to living people), what the Romans called one's genius that is gifted to one at birth and is one's personal spirit to which one must be faithful if one wishes to be born into true and creative life. If one sacrifices to one's genius, one will in return become a vehicle for the fertile creativity that the genius can bestow. A person is not a genius but a transmitter of its gifts.

Like Lawrence, Dylan has served as a vehicle for his genius. His many masks, unified by Bob Zimmerman under the pseudonym Bob Dylan, have served as ciphers for the transmission of his enigmatic and arresting art. But while the music dazzles, the "real" man behind the name can't stand up - or is it, won't? - because, as always, he's "invisible now" and "not there," as his songs have so long told us.

I wondered if my theater companions understood this, or perhaps didn't want to. Could that be because their own reality now, if viewed from then, is problematic to them? Do generations of his fans sense a vacancy at the heart of their self-identities - non-selves - as if they have been absent from their own lives while reveling in Dylan's kaleidoscopic cast of characters? Do Dylan's lyrics - "People don't live or die people just float" - resonate with them? Lacking Dylan's artistry, are many reluctant to ask why they are so intrigued by the legerdemain of a man who insists he is absent? Has a whole generation gone missing and trying to find where they went?

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).