The F*cked Up World of Frank Gehry

by John Kendall Hawkins

When I was a child I was just in love with the shapes of the world. I really got off on looking up at clouds, especially cumulus, watching them drift and build and morph against an azure sky. Similarly, I was fascinated by the forms and functions of local and city skyscapes, simple local churches that quietly summoned its likely-lost sheep to comfort them with homilies and bromides for their sins -- everybody knows that a church is the spiritual compass point of the village, the steeple as the center. Sanctus simplicitus.

And I was just in awe of cathedrals more than anything -- outside, gargoyles, arches, spans, flying buttresses, and a general impression of safety; inside, light coming through stained-glass windows into a shared darkened space in which all are equal before the Law of God, ornate columns, altars and rituals and rites, and a sepulcher sense of mad baroque or gothic features brought together in an intense energy storm of the beautiful and the terrifying. And, sitting there, breathing in the suspirations of past generations now mixed with your own, that had lingered, while you considered how families of constructors may have spent a hundred or more years completing the structure. Bristol Cathedral started in 1218 and was not finished until 1905 - 688 years! Sanctus grandissimus.

It was some youth I had, wondering. One of my Marine uncles suggested to my Ma that she buy me a Johnny 7 to play cowboys and Indians with. We called them ind'gens back then, instead of Indians. We called them Indians because, a pal told me, Columbus was sh*t-faced and took the wrong turn on the high seas. I sometimes wonder what the look on chief Sitting Bull's face at Little Bighorn would have been like had Custer pulled out a fully locked-and-loaded Johnny 7. Instead, the arrogant Custer got scalped and they cut off blondie's nutsack. I loved the shape of the tepees, smoke circling out of the funnel at dusk. And surprisingly functional, given the form. And the funnels remind me of the woo-hoo crazy architect Frank Gehry's wayward work.

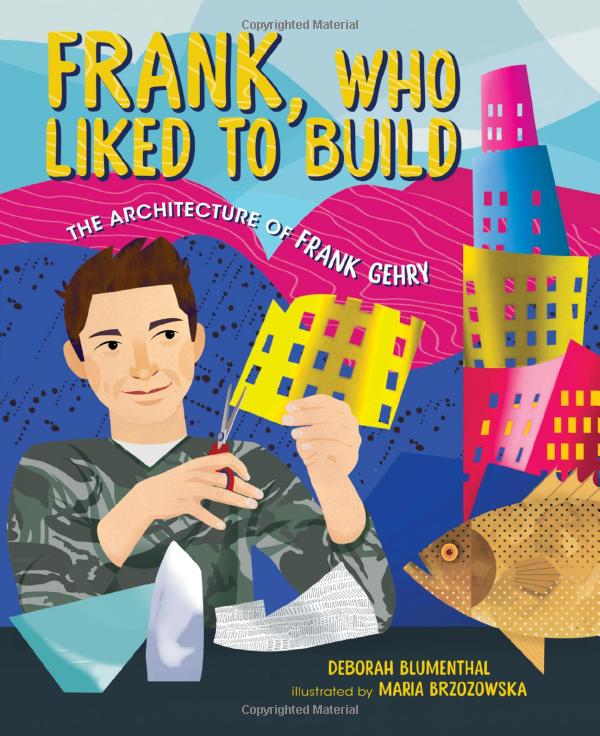

There's a new children's book out (ages 4-9) about Gehry's work (and an accompanying audiobook) that is short, sweet and inspiring, Frank, Who Liked to Build: The Architecture of Frank Gehry (Kar-Ben, 2022, 32 pages). The story is by Deborah Blumenthal. It's illustrated by Maria Brzozowska. The colorful little book tells children (and adults) about the inspiration for the extraordinary designs that Gehry brought to fruition from sketches to eye-popping designs livening up real urban landscapes. Gehry tells us about his hard-ass parents and his grandma, who would give him blocks of wood from the kindling bag that he would use to build cities and ignite his imagination for further florid designs.

Frank, Who Liked to Build begins: "Imagine a building with sloping silver skin that seems to shiver in the wind. Or another with billowy blanket walls big enough to hide a family of dinosaurs. And who made them? Frank Gehry. An architect." An architect is a wonderful thing. After I grew out of my Johnny 7 period, the nice young Jewish lady on the first floor of our three-decker in Mattapan, who had been watching out the window, apparently, as I played kickball with Jeffrey Rosenbaum from across the street, and mildly slapped him across the face after a perceived infraction of loose rules, sending him home teary, him looking back at me with a reductionist posture (it seemed), and his mother would never let him play with the only goyim in the all-Jewish neighborhood. I spent most of my time afterward in my bedroom, alone, listening to the latest pop music. The Beatles had just put out "Love Me Do."

One day the nice lady on the first floor saw me sitting on the front steps, moping, and said to me, "Johnny, I'd really like to know what makes you tick," referring to the slap heard around the local insular world. "Me, too," I mumbled hoarsely, like Froggy from the Little Rascals. And next thing I know she went inside and came back with a book and handed it to me, Architecture As A Space. Beyond my years at that time, but led, eventually, to my falling in love with the Gothic and cathedrals and Notre Dame, in particular. Form and function. Bristol Cathedral took more than 600 years to build. How about that! But I never played with Jeffrey again, and took the nice lady's rebuke so seriously that later, when I matriculated, I majored in philosophy, to look into how things tick. I didn't like what I saw, I'll tell you that.

But Frank had his problems, too. He was a boy genius, doodling frantic designs that evoked the word: haywire. His parents, Blumenthal and Brzozowska tell us, were not dazzled, we're told: "Frank's father wasn't impressed. He thought I was a dreamer, Frank said. He didn't think I would amount to anything. Neither did my mother. Those thoughts haunted him his whole life. Dreamers keep dreaming and playing. Frank made rooftops that bend and sway." I felt bad for young Frank; he must have felt like his world was topsy-turvy, uncentered and cast away like a crumpled up draft of an essay. Later his inner hostility at such ma/paternal rejection seems to have been reflected in his rendition of MIT's Stata Building that looks like some God-chik punched form-and-function right in the face.

Luckily for Frank, his Nana came through with sunshine and praise and encouragement, leading him away from a potentially embarrassing Meyer Lansky-esque future, him telling a pretty bank teller one day that the robbery note says "I've got a gun" not, as she insists, gub. (Frank even became a truck driver for a while to show just how close the devil's deal was.) Blumenthal displays the grandmother's loving care for the boy wonder: "[His grandma would give him] chunks of dough "to play with when she was baking Challah"that became Frank's homemade clay"so he could change the shape of things."

And she brought home carp from the market and kept them fresh in the water-filled bathtub. We're told by the author:

Frank kept those fish alive in his fish lamps, in his curving and swerving jewelry and in giant fish sculptures with shiny skin. And maybe the graceful way the carp swam and swam and his love of sailing in the water, explaining the curves in his buildings like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao.

Blumenthal's gentle lyricism brings out the playful nature of Gehry's complex simplicity. It has been said often enough that humans have mimicked the works of nature in developing many of their ideas. And, in this sense, Gehry's work, counterintuitively, seems like a return primitivist forces at play. Either that or his work is a massive display of autism. A boy blowing bubbles that he will live in. And not quietly. Amounting to nothing -- inventively and prolifically.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).