Aside from death, pain is the great leveller in people's lives. Shakespeare referred to la petite mort of sexual intercourse as a state as close to the heaven on earth that most of us are likely to reach. Pain is death's orgasm; and, people will do or say anything to stop it when being tortured. Ecstasy and agony live at the extreme borders of our banal being in the world. But maybe worse than the banality we quietly suffer through, we can slip into that solitary malaise that numbs us and our senses to the events, big and small, unfolding before us.

Big events happen and we tell ourselves Never Again. The first born Cain kills Abel and is exiled, our backs turned to him. The Bombs drop on the Japs, atom and hydrogen, and, 'become as Gods' and awed at our own power, we promise to do our best to never use them again and build a security apparatus to ensure that the Bad Guys don't steal our secret. We come across the depravity of human suffering and misery exemplified by the Holocaust and the death camps and afform with all our might we mustn't ever let it happen again. But we do let it happen again. We will forget even the worst atrocities. These days we call it empathy fatigue, but it's a solid part of the human story, barely improved upon, going back, in the West to our origins in the Fall, and the establishment of pain in labor as the price of giving birth.

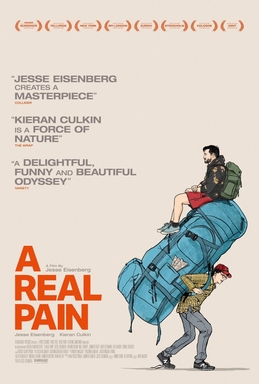

Well, this we all know, and have visited this museum of human flaws many times. Who isn't tired of the reification and/or relativizing of our species' misery? I was thinking of all this as I began watching A Real Pain (2024), a Holocaust comedy, starring Jesse Eisenberg, as David Kaplan, and Kieran Culkin, as Benji Kaplan. The film is written and directed by Eisenberg. The once-close, now distant, cousins reunite at JFK airport to go on a trip to Poland to visit the childhood home of their late grandmother and to connect with their Jewish heritage. The pair go on an expenses-paid Nazi German Holocaust tour by train through the beautiful countryside of Poland.

Culkin's Benji is the same fractured, thoughtfully sad, but spontaneous, character he is as Roman Roy in the HBO series, Succession ((2018-2023). Eisenberg's David is a quiet, far cry from the dynamic smarty pants Mark Zuckerberg that he plays in The Social Network (2010); here is an online ad salesman. Early on, Benji has a go at David's line of work: "That's cool, that's cool - you're like making the world go round. It's not your fault, you're just part of a fucked up system." The successful, conservative family man is thrown off by Benji's disaffection with the System, but also enthralled by his charisma that plays somewhat like Hamlet's antic/melancholy disposition. Benji has attempted suicide in the past, which led to their alienation from each other, as David couldn't hack Benji's sadness and they stopped calling each other. Still, the two are gentle with each other. Two Jews on The Pilgrimage.

When the two meet up at JFK to begin their trip, Benji has already been there for several hours. He is bearing a huge backpack, as if carrying his world with him, while David has just enough luggage for the trip. When a surprised David inquires about Benji's presence at JFK so long before the flight, he comes back with hw it's a great way to meet new people:

You meet the craziest people here. I met this guy Kelvin who was from Brunei. f*cking Brunei! I never met anyone from Brunei. Dude was telling me all about his business, I think he's actually an arms dealer but he seemed totally at peace with the whole thing.

This sounds to me like vintage Woody Allen shtick. Benji seems like he would be fun to be around. Dry, but not sardonic.

The Holocaust Tour group travels by train. This irony is not lost on the pair, although the group seems blithely past the historical significance of the mode of transport. Only Benji picks up on the connection to cattle cars. This seems to be one of the points of the film; to show how the most evil pain can lose its luster and mothball in the museumization of its artifactual interest. In planning and writing the film, Eisenberg told Conde Nat Traveller that he didn't want to just write another Holocaust film:

I wanted the portrayal of Poland in general to feel beautiful and dynamic and colorful and all the things that I feel when I'm there. I feel it's too often depicted as bleak, fetishizing its Eastern European Soviet communist history and fetishizing the horrors of the war.

The viewer somewhat anticipates that the trip will end at a death camp and we will be cued to sob for the horror caused by Nazi pain merchants, but when they finally arrive at Majdanek, after stops in Warsaw and Lublin, there is no grand panoramic view or even many details presented in the film: a box of shoes fills in for the metaphors required: we know where the shoes came from and what happened to their wearers. It's a minimalistic pilgrimage, pain-wise.

The tour group is led by James, a non-Jew from England, who is Oxford-trained and knowledgeable about the Holocaust. A real nice guy. And he exudes good intentions, and remorse from the heart for all of us, and is not someone who will forget the atrocities of World War II. The group includes Mark and Diane, two recently retired Jews with roots in Poland and France; Marcia, whose mother was a survivor of the camps; Eloge, a sweet Rwandan, recently converted to Judaism; and, the Kaplan cousines. As the group shares introductions, James tells them:

I am obsessed with this part of the world and, in particular, the Jewish experience, which is fascinating and tragic and beautiful. I'm usually the only non-Jew on these trips, so please feel free to correct me on anything that feels inauthentic to you or your family's experience.

Wonderful chap, well-spoken, but also a little on the ChatGPT side; maybe a little too polished. He brings them first to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Memorial, because he wants the group to first understand that many Jews heroically fought back against the Nazis and didn't just go gentle into Elie Wiesel's Night. James says, with feeling:

This is going to be a tour about pain, of course. Pain and suffering and loss, to be sure, but it must also be a tour that celebrates a people. A most resilient people.

Who in the cinema can say they are not choked up? Except maybe the bevy of fascists, a couple of rows down to the right, who breath like panting dogs. But that might have been the acid. I watched a film called Invasion of the Body Snatchers once and could have sworn there was a scene where a dog shows up with a human head. Goddamn, the pusher man.

The tour is going well enough; folks are free and easy, pose for snaps for Instagram and the like. But it strikes Benji as lacking emotional authenticity. In the graveyard at Lublin he complains to James, "I mean, you know your sh*t, don't get me wrong"But it's just like, the constant barrage of stats is kinda making this trip a little cold, you know?" David is horrified at this breach in etiquette. Benji continues, "Don't take this the wrong way or anything, but we've just been going from one touristy thing to another, not meeting anyone who's actually Polish." James is apologetic. The group, having been broken in by Benji's charm, is okay with Benji's outburst and his need for authenticity.

Benji is playful and spontaneous and, for David, scary. David can't relate to Benji's impulsiveness, especially around the idea of suicide. Benji sneaks marijuana past the TSA inspector at the airport, chatting her up with his charm, while David fears they will be stopped and arrested. In a hotel in Poland, Benjo wants to smoke a doobie on the roof and breaks through an alarmed door to get to the staircase (the alarm's not working). And on a train, he leads them past a ticket inspector and they hide in first class. Benji would have enjoyed Abbie's street theatre antics and definitely would have stolen Steal This Book. David would have bought the book.

The film reminds one that emotional truth is not only a valuable mode with which to perceive historical narratives and experiences, it's the only way. The information that James provides is impressive but hollow, and, as Benji points out, eventually overwhelming with its factoidiness. One needs to be there, rather than tour there and take snaps. It's a balancing act absorbing all the horror of the camps, and reflecting on the Jewish experience and how influential it has been in the West by way of the three Abrahamic religions (Je suis juif, brother), and becoming overwhelmed and deadened by images in our head from Shoah or other footage of bulldozers pushing naked human bodies into mass graves. There is only so much one can take. And now that you see the writing on the wall for the species".

This take on the Jewish experience also amplifies the holocaust taking place in Palestine right now. The ironies -- or, maybe worse, the introjection of the cruelties meted out to Jews now resurfacing as payback. Isn't Gaza like the ghetto? Isn't the Promised Land for all the Judaics -- be they Jewish, Christian, or Islamic? WTF?

Chopin and other classical composers feature throughout the film. It made me nostalgic and feeling neglectful of my piano music listening years. It reminded me that it has been ages since I sat down and listened to Chopin's ballades, e'tudes, nocturnes, preludes, and waltzes. I used to love this stuff. I tried to get back into Schumann's Fantasiestucke, Op. 12 a few years ago -- I just love the stuff -- but I was listening through YouTube and the f*ckers placed ads between each song. Isn't that a kick in the head? David might be the kind of guy messing up my mental coif with ads.

A Real Pain is a reminder to seek out sensory authenticity and to get off the grid of farm fed emotions. In the end, David slaps Benji in the face, as if to say, wake up. But Benji's the woke one. David apologizes and they hug. David offers to drive him home, but Benji stays behind at JFK with his massive backpack, presumably meeting new people. Coming and going.