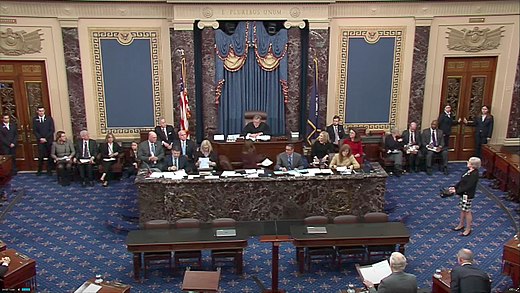

Chief Justice John Roberts presides over the impeachment trial of Donald Trump.

(Image by Wikipedia (commons.wikimedia.org), Author: United States Senate) Details Source DMCA

As I write this, the US Senate is cranking up for its trial of former President Donald J. Trump. The House impeached Trump on January 13, a week before the end of his term, on one article charging him with "incitement of insurrection" in the form of the January 6 riot at the US Capitol.

Even Trump's most ardent opponents hold out little hope of conviction. That would require the votes of 67 US Senators, at least 17 of whom would have to be Republicans. And 45 of 50 Republican Senators have already voted against holding the trial at all, on grounds that it would be "unconstitutional" because Trump is no longer president.

It's not unconstitutional. The Constitution's plain language, precedent in both US and pre-revolutionary British practice, and a common sense holding that the founders would not prescribe a penalty (disqualification from future office) that could be rendered toothless by resignation, make it clear that an official can be tried (and impeached) after leaving office. In fact, some Republicans advocated doing exactly that to former Vice-President Joe Biden only months ago over his alleged corruption vis a vis Ukraine and Burisma.

Nor do other Republican excuses -- that trying the impeachment would violate Trump's First Amendment rights, for example, or that Chief Justice John Roberts is constitutionally required to preside at the trial -- hold water. Impeachment is a political, not criminal, proceeding, to which the First Amendment is irrelevant. The Chief Justice presides at the trials of presidents, not former presidents (Democratic US Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont will preside at Trump's trial).

Nor do those excuses explain why Republicans will almost unanimously vote to acquit, any more than an honest belief in Trump's guilt explains why Democrats will unanimously or almost unanimously vote to convict.

What does explain the nearly inevitable outcome? That the trial is, as I mentioned, a political proceeding.

House Democrats voted to impeach, and Senate Democrats will vote to convict, because they believe doing so improves their personal political prospects and the political prospects of their party.

Most House Republicans voted against impeachment, and most Senate Republicans will vote to acquit, because they believe it's the least bad option available where their personal and party political prospects are concerned.

"Least bad" isn't "good," but this is a "heads the Democrats win, tales the Republicans lose" situation.

Voting to convict exposes Republican Senators to primary challenges from Trump loyalists come next election, and possibly even a fatal split in the GOP itself.

Voting to acquit leaves them right where they were, with the rotting albatross of the Trump presidency hanging around their collective neck. It's a tough call and probably leaves them in the congressional minority and out of White House contention for the next few years either way.

Trump's actual guilt or innocence -- which you may notice I've offered no opinion on -- is as irrelevant to his second impeachment trial as it was to his first.

The moral of the story: Politics is very expensive, but not very good, dinner theater.