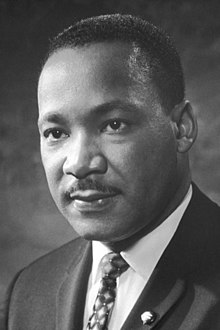

Martin Luther King%2C Jr..

(Image by Wikipedia (commons.wikimedia.org), Author: Nobel Foundation) Details Source DMCA

Duluth, Minnesota (OpEdNews) May 28, 2023: The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968; Ph.D. in theology, Boston University, 1955) is the subject of the American Jewish journalist Jonathan Eig's massively researched and admirably lucid new 680-page 2023 book King: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Because Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis in 1968, he was a martyr for black civil rights - and for non-violent protest.

No doubt the Jim Crow practices in the South that inspired his activism are mostly historical memories today - perhaps in part thanks to Dr. King's non-violent protests. But slavery has been described as America's original sin, and the scars of slavery and racial inequality are still with us today. Consequently, I believe that the agape love that Dr. King advocated for non-violent protest can still be advocated today for those who want to fight racial inequality in American society today.

Disclosure: Twice in my young life, I heard the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., speak in person. (1) I heard the Baptist minister speak to in person on the campus of Saint Louis University, the Jesuit university in St. Louis, Missouri, on Monday, October 12, 1964 - just days before it was announced that Dr. King had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize - the topic of Eig's Chapter 31: "The Prize" (pp. 385-403); and (2) I also heard Dr. King speak in person on March 25, 1965, in Montgomery, Alabama, at the conclusion of the famous march from Selma, Alabama - the topic of Eig's Chapter 35: "Selma" (pp. 426-438).

I was inspired by Dr. King's talks to devote ten years of my life (1969-1979) to teaching about one thousand black inner-city youth, alongside about one thousand white students, in the context of open admissions in the City of St. Louis and in New York City (in 1975-1976).

Based on my experience of teaching black inner-city youth in the context of open admissions, I published my controversial article "IQ and Standard English" in the NCTE journal College Composition and Communication, volume 34 (1983): pp. 470-484. In it, I argue that the black and white IQ differences are most likely due to environmental and cultural differences, not to genetic and hereditary differences - to counter Arthur R. Jensen's suggestion that they are due to genetic and hereditary differences.

Also see my follow-up article "A Defense for Requiring Standard English" in Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory, volume 7 (1986): pp. 165-180. It is reprinted in the book Rhetoric: Concepts, Definitions, and Boundaries, edited by William A. Covino and David Jolliffe (Allyn and Bacon, 1995, pp. 667-678).

In any event, Eig's book contains a "Prologue" (pp. 3-6), 45 crisply written chapters (pp. 9-552), and an "Epilogue" (pp. 553-557). His book contains "Notes" keyed to page numbers (pp. 559-632) and an "Index" (pp. 643-669). Eig "interviewed more than two hundred people" for this book (p. 634; he lists their names on pp. 639-642).

Certain persons in Eig's book are widely known (e.g., President John f. Kennedy, Attorney General Robert f. Kennedy, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, President Lyndon B. Johnson). But many of the persons that Eig mentions repeatedly throughout the book are not widely known. Consequently, the "Index" is a handy resource to use to refresh one's memory of some of them.

Now, like the first Catholic president of the United States, John F. Kennedy (1917-1963), the black Baptist minister and civil rights activist was an extraordinary womanizer (the "Index" contains a sub-entry on MLK's "extramarital affairs" [p. 656]). In Eig's Chapter 23: "Temptation and Surveillance" (pp. 270-278), he says, "[Stanley] Levison points out that King and John F. Kennedy had something in common in this regard. 'Both had powerful fathers who were men of notorious sexual prowess, Levison told historian Arthur M. Schlesigner, Jr. 'Perhaps both were unconsciously driven to prove they were as much men as their fathers'" (p. 272).

Now, in Eig's Chapter 7: "The Seminarian" (pp. 74-80), he says that at Crozer Theological Seminary, King wrote "'as a Christian I believe that there is a creative personal power in the universe who is the ground and essence of all reality - a power that can not be explained in materialistic terms.' History, he concluded, was guided by the spirit, not by matter" (pp. 78-79). In addition, Eig says, "He [King] continued to show particular interest in the social gospel of Walter Rauschenbusch, who argued that the 'Kingdom of God' required not only personal salvation but social justice, too. King admired Rauschenbusch's call to action and related to his sense of optimism. It is 'quite easy,' he wrote, 'for me to think of the universe as basically friendly. King believed that human personality reflected the spirit of God. But the negative corollary to that belief meant that racism, which degraded personality and denigrated human life, had to be evil. Even in the North, he experienced that evil" (p. 79).

Now, in Eig's Chapter 9: "The Match" (pp. 88-100), he says, "King chose [Boston University], in large part, for the chance to study with Edgar S. Brightman, known for his philosophical understanding of the idea of a personal God, not an impersonal deity lacking human characteristics. 'In the broadest sense,' Brightman wrote, personalism is the belief that conscious personality is both the supreme value and the supreme reality in the universe.' To personalists, God is seen as a loving parent, God's children as subjects of compassion. The universe is made up of persons, and all personalities are made in the image of God. The influence of personalism would support King's future indictment of segregation and discrimination, 'because personhood,' wrote the scholars Kenneth L. Smith and Ira G. Zepp, Jr., 'implies freedom and responsibility'" (p. 89).

For further information about Brightman, see the Wikipedia entry about him.

For further discussion of personalism, see the Wikipedia entry on Personalism.

Now, in Eig's Chapter 11: "Plagiarism and Poetry" (pp. 107-112), he says, "For his doctoral dissertation, King compared conceptions of God presented by two theologians Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman. King criticized both Tillich and Wieman for their distance from personalism. Tillich ascribed personality only to beings, not to God, while Wieman described God in relatively depersonalized terms, as an 'integrating process.' King rejected both ideas, saying human fellowship with God could only occur when both parties to the relationship possessed understanding and respect. Ascribing a human personality to God, King argued, in no way implied a limitation of God's power" (p. 110).

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).