The Global Saudi Dawa Project: An Interview with Krithika Varagur

by John Kendall Hawkins

In Krithika Varagur's own words:

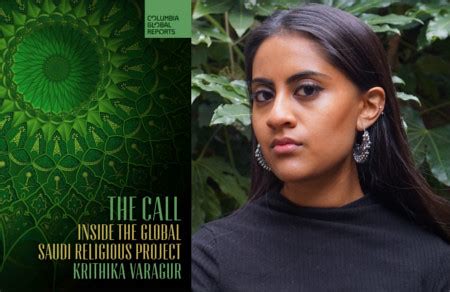

Krithika writes the At Work column, about the quirks, realities and frustrations of the workplace today. She is a reporter and author who has covered topics ranging from dating apps to counterterrorism. She spent four years as a foreign correspondent in Southeast and South Asia, reporting on religion, politics and fundamentalism, especially in Indonesia, where she was a correspondent for the Guardian. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Atlantic, the New York Review of Books, the Financial Times and more. She is the author of The Call: Inside the Global Saudi Religious Project, published in April, which she reported from Indonesia, Nigeria and Kosovo. Krithika graduated from Harvard and has a master's degree from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, where she was a Fulbright scholar.

from the WSJ

Last year Krithika published The Call: Inside the Global Saudi Religious Project . Essentially, the book describes the deliberate spread of Sunni Islam around the globe, with all the political, economic and religious implications that brings. Wahhabism, the most conservative version of Islam and sharia law, are the focus of her attention. She shows how the Kingdom has proselytized ( dawa ) its value through a variety of means (discussed below). She addresses the Saudi-American post-9/11 relationship, including terrorism and its counter. Mainly, her work describes a society still internally fractured along religious/political lines -- between the ultraconservative and ancient Wahhabi sect and the House of Saud -- that leads to contradictions much of the western world is cognizant of.

Below is an interview I conducted with Krithika a few days ago:

Could you summarize the message of The Call ?

The Call is about what we talk about when we talk about Saudi money. It's become kind of a chestnut in the post-9/11 world I grew up in that Saudi Arabia funds terrorism, due in no small part because 15 of the 19 9/11 hijackers were Saudi nationals. And many other things in the era after that made it clear that there was a link between this kind of Saudi propagation of Wahabbi Islam...I wanted to make this Saudi project ...more concrete. So I reported about it from across the Muslim world, in places that many Americans still don't think of as the Muslim world -- Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim country, Nigeria, and Kosovo, a small country in the Balkans. And I talked with people who actually carried out this Arab Project.

So I have to say the biggest takeaway from the Saudi proselytization project, the dawa project, which started in 1960s and continues up until the years to today, is not one thing; it comes from many places, including government ministries, powerful individual royals, multinational charities headquartered inside of Saudi Arabia, and so on, and it is had many diffuse effects. So, terrorism is just one of them, and honestly a small one in terms of the number people affected. It's also about political effects, such as propping up Islamist political parties, changing Islamist landscapes like propogating the ...Salafi movement, and filling in the spiritual life, in some way, in a once war-torn nation like Kososvo. So, my book is about looking at the Saudi dawa project in a more nuanced way and taking a wide variety of ... effects and ...beyond just terrorism, although I do go into Saudi extremism in case of Boko Haram in Nigeria and ISIS foreign fighters.

In The Call , you write, "What did Saudi Arabia displace when it became a leader of the Muslim world, with Western support, in the 1980s? Arab nationalism, socialism, secularism, progressivism. Saudi Arabia bet on religion and political quietism instead of progressive Muslim organizing and thus reshuffled the religious landscape of the Muslim world." There is an unsettling dimension to this dynamic relationship -- the sacrifice of progressivism --almost as if Wahhabism was influencing the direction American policies, domestic and foreign, would take from the 80s on. Comment?

I wouldn't say that Wahhabism was influencing American policy but that the Saudi Project in the second half of the 20th century dovetailed a lot with the American Project abroad in the Cold War era. So Saudi Arabia opposed communism, progressivism, Arab socialism at the time as deeply threatening to absolute Sunni bureaucratic monarchy and ...the US opposed communism as part of the Cold War against the USSR. ...Lot of affinities based upon the pre-existing business relationships between Saudis and America.

Given the "damning" evidence of Saudi financing of 9/11, what exactly is the nature of their long term relationship with America? What do they want from each other? How can Americans still justify it?

The reason why 9/11 wasn't the nail in the coffin of the US-Saudi relationship was because, despite what we found in the 9/11 commission's report, was that in the post-9/11 world they remained an important counterterrorism partner for us. In fact, in 2003 to 2004, al Qaeda bombed targets inside of Saudi Arabia too. So they became victims of al Qaeda as well. Keep in mind,Bin Laden was of Yemeni origin and came from a very wealthy Saudi family and he later distanced himself from the Kingdom and criticised the monarchy as being insufficiently Islamic. The terrorism that led to 9/11 from al Qaeda was also a threat to Saudi Arabia itself, which is a little ironic given the links to extremism that I outline in my book. We continue to have this close...partnership with them, we couldn't exactly sever that cord -- we continued to have oil interests with the country and continued to sell massive amounts of arms to them -- so all of those things continued well into the 21st century ...

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).