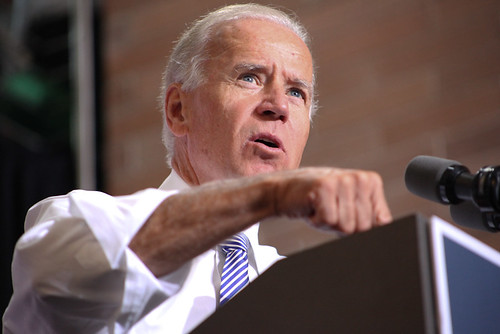

In a party that officially condemns dog-whistle appeals to racism, Joe Biden is running on Orwellian eggshells. Whether he can win the Democratic presidential nomination may largely depend on the extent of "doublethink" that George Orwell described in 1984 as the willingness "to forget any fact that has become inconvenient."

It is an inconvenient fact that Biden has a political history of blowing into dog-whistles for racism. More than ever, the Democratic electorate is repelled by that kind of pitch. If his dog-whistling past becomes a major issue, the former vice president and his defenders will face the challenge of twisting themselves into rhetorical pretzels to deny what is apparent from the video record of Biden oratory on the Senate floor that spanned into the last decade of the 20th century.

Biden is eager to deflect any prospective attention from his own history of trafficking in white malice and racial division. When he tweeted this week that "our politics today has become so mean and petty -- it traffics in division and our president is the divider in chief," Biden was executing a high jump over the despicably low standards set by Donald Trump.

A key question remains: Does it matter that Biden was a shrill purveyor of tropes, racist stereotypes and legislation aimed at African Americans? During pivotal moments in the history of race relations in this country, from the 1970s to the 1990s, Biden's hot air manifested as pitches to white racism. From the outset of his career on Capitol Hill, he even stooped to reaching out to some of the worst segregationist senators from the South to advance his legislative agenda against busing.

As Adolph Reed and Cornel West noted this month in the Guardian, Biden began his racially laced approach to lawmaking soon after arrival in the Senate, when he "earned sharp criticism from both the NAACP and ACLU in the 1970s for his aggressive opposition to school busing as a tool for achieving school desegregation."

That was no fluke. "In 1984," Reed and West recount, Biden "joined with South Carolina's arch-racist Strom Thurmond to sponsor the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which eliminated parole for federal prisoners and limited the amount of time sentences could be reduced for good behavior. He and Thurmond joined hands to push 1986 and 1988 drug enforcement legislation that created the nefarious sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine as well as other draconian measures that implicate him as one of the initiators of what became mass incarceration."

It's likely that no lawmaker did more to bring about the mass incarceration of black people during recent decades than Joe Biden. In an understated account last week, The Hill newspaper reported that Senator Biden "was instrumental in pushing for the [1994] crime bill, which critics have said led to a spike in incarceration, particularly among African Americans."

Yet Biden is now eager to project an image as a longtime ally of people of color. In short, journalists Kevin Gosztola and Brian Sonenstein wrote recently, he is in a race between his actual past and his PR baloney.

As the leading advocate for what became the infamous 1994 crime bill, Biden stood on the Senate floor and declared: "We must take back the streets. It doesn't matter whether or not the person that is accosting your son or daughter or my son or daughter, my wife, your husband, my mother, your parents, it doesn't matter whether or not they were deprived as a youth. It doesn't matter whether or not they had no background that enabled them to become socialized into the fabric of society. It doesn't matter whether or not they're the victims of society. The end result is they're about to knock my mother on the head with a lead pipe, shoot my sister, beat up my wife, take on my sons."

And Biden proclaimed with fervor that echoed right-wing dogma: "I don't care why someone is a malefactor in society. I don't care why someone is antisocial. I don't care why they've become a sociopath. We have an obligation to cordon them off from the rest of society."

Paste writer Shane Ryan pointed out the unsubtle subtexts of Biden's speechifying: "This is the language of demonization, and even without the underlying racial element, it would be offensive to describe Americans this way, and to brush aside the societal conditions that lead to violent crime as though they're irrelevant. But, of course, the racial element is not just present, but profound. It's impossible to read these remarks, complete with dehumanizing rhetoric, without coming to the conclusion that Biden is, in fact, talking about black crime."

At the time, even some of the members of Congress who ended up voting for the crime bill loudly warned about its dangerous downsides. One of them was Bernie Sanders (who I actively support in his run for president). While swayed by inclusion of the Violence Against Women Act in the bill, Sanders said in an April 1994 speech on the House floor: "A society which neglects, which oppresses and which disdains a very significant part of its population -- which leaves them hungry, impoverished, unemployed, uneducated, and utterly without hope -- will, through cause and effect, create a population which is bitter, which is angry, which is violent, and a society which is crime-ridden. And that is the case in America, and it is the case in other countries throughout the world."

In 2016, Biden was continuing to defend his key role in passage of the landmark crime bill. During recent months, gearing up for his current campaign, Biden acknowledged some of the law's negative effects while still defending it and denying its huge impacts for mass incarceration. And Biden has avoided copping to -- much less expressing remorse for -- the toxic, racially laced rhetoric that he used to promote the bill. He simply refuses to renounce the Senate-floor oratory that he deployed to propel the legislation to President Clinton's desk.

Unfortunately for Biden, online video is available that conveys not only his words but also the audibly arrogant tone with which he delivered them.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).