KN: The book titled “The Melancholy History of Soledad Prison,” by Min Yee, documents how Hugo Pinell was one of the original members of the Black Movement, led by George Jackson and others in Soledad Prison. At that time, it wasn't safe for Blacks to walk the yard. The collusion between the racist, KKK-type guards and white racist prison gangs was horrendous. These conditions were horrible.

Yogi was eventually transferred to San Quentin, and was there on August 21, 1971, when George was assassinated. That day, in what was described by prison officials as an escape attempt, George allegedly smuggled a gun into San Quentin in a wig. That feat was proven impossible, and evidence subsequently suggested a setup designed by prison officials to eliminate Jackson once and for all as they had tried numerous times. On that fateful day, three notoriously racist prison guards and two inmate turnkeys were also killed. According to an eye witness, when Jackson was shot while running on the yard, he got up instantly and dived in the direction of some bushes. He was subsequently murdered while lying on the ground wounded.

Six Black prisoners were charged with murder and assault. Hugo Pinell, Fleeta Drumgo, David Johnson, Luis Talamantez, Johnny Spain, and Willie Sundiata Tate became known as the “San Quentin Six.” Johnny Spain was the only one convicted of murder. The others were either acquitted or convicted of assault. Hugo is the only one remaining in prison, and badly needs our support.

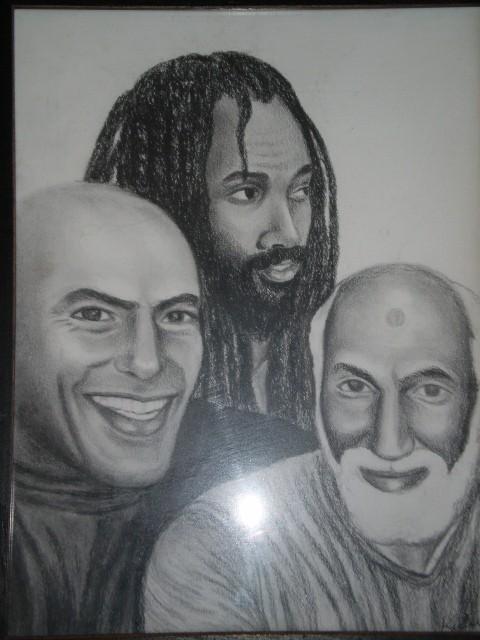

(ARTWORK BY KIILU NYASHA): From left to right: Hugo "Yogi Bear" Pinell, Mumia Abu-Jamal, and Albert "Nuh" Washington

HB: Tell us about Ruchell Magee.

KN: I first met Ruchell in the holding cell of the Marin County courthouse in the Summer of 1971. I found him to be soft-spoken, warm and a gentleman in typically Southern tradition. We’ve been in correspondence pretty much ever since. I was then working for The Sun Reporter, and covering the pretrial hearings of Angela Davis and Ruchell Magee. By 1971, Ruchell was an astute jailhouse lawyer. He was responsible for the release and protection of a myriad of prisoners benefiting from his extensive knowledge of law, which he used to prepare writs, appeals and lawsuits for himself and many others behind the walls.

Ruchell was fighting charges of murder, conspiracy to murder, kidnap, and conspiracy to aid the escape of state prisoners. Although critically wounded on August 7, 1970, he was the sole survivor among the four brave Black men who conducted the courthouse slave rebellion, leaving him to be charged with everything they could throw at him. On August 7, 17-year old Jonathan Jackson raided the Marin Courtroom and tossed guns to prisoners William Christmas and James McClain, who in turn invited Ruchell to join them. Rue seized the hour spontaneously as they attempted to escape by taking a judge, assistant district attorney and three jurors as hostages in that audacious move to expose to the public the brutally racist prison conditions and free the Soledad Brothers.

McClain was on trial for assaulting a guard in the wake of Black prisoner Fred Billingsley’s murder by prison officials in San Quentin in February, 1970. With only four months before a parole hearing, Magee had appeared in the courtroom to testify for McClain.

The four revolutionaries successfully commandeered the group to the waiting van and were about to pull out of the parking lot when Marin County Police and San Quentin guards opened fire. When the shooting stopped, Judge Harold Haley, Jackson, Christmas, and McClain lay dead; Magee was unconscious and seriously wounded as was the prosecutor. A juror suffered a minor injury.

Magee had already spent at least seven years studying law and deluging the courts with petitions and lawsuits to contest his own illegal conviction in two fraudulent trials. As he put it, the judicial system “used fraud to hide fraud” in his second case after the first conviction was overturned on an appeal based on a falsified transcript. His strategy, therefore, centered on proving that he was a slave, denied his constitutional rights and held involuntarily. Therefore, he had the legal right to escape slavery as established in the case of the African slave, Cinque, who had escaped the slave ship, Amistad, and won freedom in a Connecticut trial. Thus, Magee had to first prove he’d been illegally and unjustly incarcerated for over seven years. He also wanted the case moved to the Federal Courts and the right to represent himself.

Next Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).