>

Industrial-scale intermittent wind power:

recognizing its unreliability before we spend billions; a column about nature and technology

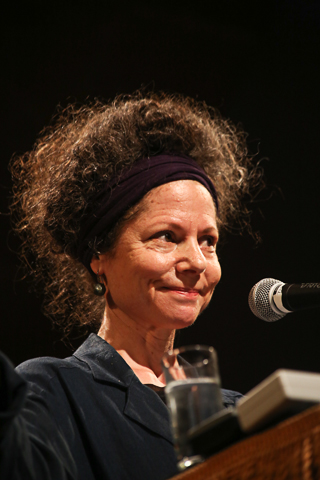

by Katie Singer

Call this a letter to President Biden. To begin, let me appreciate that your American Jobs Plan recognizes connections between our economy, energy needs, greenhouse-gas emissions and infrastructure. I am a citizen-researcher and writer, deeply concerned about life on Earth, eager for comprehensive, due-diligent evaluations of alternative energy before we commit billions to their development.

I recognize that our society depends on safe, reliable, and affordable electric power, and that to reduce our global climate impacts, we need to reduce our greenhouse-gas emissions, drastically.

Industrial wind facilities are now the country's fastest-growing energy source. Proponents claim that wind energy is "green," "clean," "zero-emitting"--and that it will improve host communities' economies.

To initiate a due-diligent evaluation of industrial wind turbines (IWTs), let's ask: Are these claims true? What are industrial wind turbines' (IWTs') unintended consequences?

To answer these questions, we'll need people who are not industry lobbyists to evaluate wind turbines from their cradles to their graves. We'll need to learn about the rare-earth elements extracted for turbines. Consider studies about IWTs' impacts on climate. Hear from folks who've lived near an industrial-wind facility. Read about IWTs' impacts on wildlife and farming. Learn how IWT installations impact local economies and what happens to wind turbines at the end of their usable lives. Then, legislators can make informed votes about whether or not to spend billions on wind energy.

The parts

A wind turbine includes the tower, a foundation, blades and a nacelle.

(The nacelle holds the gearbox, which rotates and generates energy, then

converts it into electricity.) These four parts contain more than 8000

different components, many of which are made from steel, cast iron,

concrete and rare-earth elements. [1] When turbines are installed

offshore in deep water, their platforms also may require cables that

anchor them to the seabed.

Turbines require lubrication. On average, a 5-MW (megawatt) turbine holds 700 gallons of oil and hydraulic fluid; like car oil, these need replacing every nine to 16 months. [2]

When the industry claims that a 5-MW wind facility can power 3200 homes, it usually omits the word "intermittently." Because wind blows intermittently, IWTs cannot provide uninterrupted, reliable power to a single home, hospital, smelter, factory, data center, 4G cellular site, 5G cellular site, [3] or bitcoin mine 24/7, 365 days each year. IWTs need continuous backup power available 100% of the time. Usually, natural (fracked) gas, a fossil fuel we aim to reduce, provides backup to wind energy. When Texas temperatures froze last February, so did the turbines. Utilities did not have sufficient natural-gas backup to keep electricity available.

To avoid repeating that failure, let's recognize every wind complex typically requires wind+gas. Let's also recognize studies that show wind+gas packages can produce more CO2 than gas alone. [4]

Manufacturing

Mostly, a wind turbine's tower, nacelle and foundation are made of steel

and concrete. Every ton of steel produced emits about 1.85 tons of CO2. In

2018, this amounted to eight percent of global emissions. Steel

production generates wastewater containing cyanide, sulfides, ammonium,

ammonia and other carcinogenic organic compounds. How can we call such

toxic stuff "clean?" [5]

In a 5-MW turbine, the tower weighs about 400 tons (363 metric tons), the nacelle 300 tons (272 metric tons), and the three blades can total 54 tons (49 metric tons; 108,000 pounds). The foundation weighs several thousand tons. An offshore foundation can weigh between 500 and 8,000+ tons. [6]

Blades are made of wood, fiberglass and carbon fiber (petroleum-based plastics).

Nacelles contain dysprosium and neodymium (magnets) and other rare-earth elements. A 2-MW wind turbine contains about 800 pounds of neodymium and 130 pounds of dysprosium. At least 75% of the rare-earth market is controlled by China, which has little if any environmental regulations. Why would we invest in infrastructure that depends on an international supply chain? [7]

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).