This piece was reprinted by OpEd News with permission or license. It may not be reproduced in any form without permission or license from the source.

Republished from Rising Tide Foundation

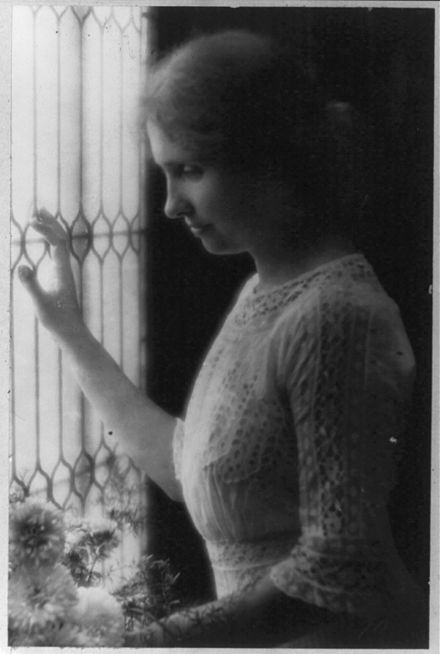

Helen Keller

(Image by Wikipedia (commons.wikimedia.org), Author: Unknown author) Details Source DMCA

"So my optimism is no mild and unreasoning satisfaction. A poet once said I must be happy because I did not see the bare, cold present, but lived in a beautiful dream. I do live in a beautiful dream; but that dream is the actual, the present - not cold, but warm; not bare, but furnished with a thousand blessings. The very evil which the poet supposed would be a cruel disillusionment is necessary to the fullest knowledge of joy. Only by contact with evil could I have learned to feel by contrast the beauty of truth and love and goodness."

- Helen Keller's paper "Optimism"

The impetus to write a paper focusing on optimism as its primary subject, is oft carried with the dual apprehension of subsequently being swiftly pelted with stones by an angry mob or exiled by critics from "civil society" as an unforgivable fool, with the understanding that those witless enough to follow such a path are always inevitably led to a most terribly tragic ruination, and thus those infected with such mental derangement are best left alone"per chance that is is infectious.

Well I should inform the reader before they go any further, that such a condition is indeed most infectious, and thus you have been warned!

Such opprobrium of optimism reminds me of Plato's dialogue "Gorgias, " where Socrates (now in his elders years) is mocked by Callicles for being a philosopher in his old age:

Callicles: And this is true, as you may ascertain, if you will leave philosophy and go on to higher things: for philosophy, Socrates, if pursued in moderation and at the proper age, is an elegant accomplishment, but too much philosophy is the ruin of human life. Even if a man has good parts, still, if he carries philosophy into later life, he is necessarily ignorant of all those things which a gentleman and a person of honour ought to know; he is inexperienced in the laws of the State, and in the language which ought to be used in the dealings of man with man, whether private or public, and utterly ignorant of the pleasures and desires of mankind and of human character in general. And people of this sort, when they betake themselves to politics or business, are as ridiculous as I imagine the politicians to be, when they make their appearance in the arena of philosophy.

Philosophy, as a part of education, is an excellent thing, and there is no disgrace to a man while he is young in pursuing such a study; but when he is more advanced in years, the thing becomes ridiculous, and I feel towards philosophers as I do towards those who lisp and imitate children. For I love to see a little child, who is not of an age to speak plainly, lisping at his play; there is an appearance of grace and freedom in his utterance, which is natural to his childish years. But when I hear some small creature carefully articulating its words, I am offended; the sound is disagreeable, and has to my ears the twang of slavery. So when I hear a man lisping, or see him playing like a child, his behaviour appears to me ridiculous and unmanly and worthy of stripes. And I have the same feeling about students of philosophy; when I see a youth thus engaged,the study appears to me to be in character, and becoming a man of liberal education, and him who neglects philosophy I regard as an inferior man, who will never aspire to anything great or noble. But if I see him continuing the study in later life, and not leaving off, I should like to beat him, Socrates; for, as I was saying, such a one, even though he have good natural parts, becomes effeminate. He flies from the busy centre and the market-place, in which, as the poet says, men become distinguished; he creeps into a corner for the rest of his life, and talks in a whisper with three or four admiring youths, but never speaks out like a freeman in a satisfactory manner.

To Callicles, philosophy is an acceptable, even a necessary part of our development during youth to obtain nobility. However, it becomes something suddenly abhorrent when practised during adult years and is absolutely sickening to behold in one's elder years, to the extent that Callicles states he feels the desire to beat such a person (insinuating Socrates), for they reek of weakness and effeminacy to which he cannot stand.

In this sense, optimism shares a similar plight with that of philosophy. Optimism too is regarded as something charming and wonderful to behold in a young child and, if the child were imbued by its opposite and were mostly cynical of all things, we would think there was something most dreadfully wrong.

This is a rather curious thing since it is expected that by the time we reach adulthood, we will partake more in cynicism than of optimism, with the gap ever widening as we age. In fact, as we progress through our adult years it is most often the case that we no longer really have a concept of what optimism is, it resembling more a mirage, a dream than something tangible and partaking in reality, or at best we relegate it to "a state of mind" where one can overcome personal barriers but that is typically the extent. The majority conclude by their middle years that optimism does not really have an effect in the governance of the world that we live in - it cannot end wars, alleviate poverty or make society more just. Nobody changes themselves first to fit an optimistic future yet to become, people are pragmatists and will only change if there is something to be gained, "the proof is in the pudding" so to speak.

If this is truly the state of affairs, and the world is governed by selfish pragmatism, why do we encourage our children to dream, to believe in goodness, to oppose injustice and to be defenders of virtue in the world they live in? Why do we tell our children epic stories of heroism and overcoming the odds, invoking wildly vivid imaginations of fantastical upon fantastical? Why do we do such a thing if the world they will step into is truly ugly, cold, unimaginative, unremorseful and ultimately unchanging? Aren't we preparing their spirits to be shattered and broken? Are we not serving them up to be devoured? Why encourage the cultivation of something during youth, only to dismiss its application in adulthood and condemn its victims to a life of torment!?

It is a terrible thing to invoke a lively imagination, only to stifle it when it is ready to mature its meanderings into more cogent challenges as to why things are they way they are and not otherwise.

In truth, to behold a child makes us all momentary converts of optimism. A child is one of the most striking refutations of a cynical outlook of humankind, for a child is full of love, an insatiable curiosity, adventure, and is a natural rebel to anything authoritarian. Thus, many classical children's stories may be best understood as not something written for just children, but rather was written as an effect of being in the presence of a child's mind, that is, it is the child that is re-invoking the archaic relic of imagination in those adults who can "listen" and "remember" the secret language of a child's imagination.

Thus we should ask ourselves, why do we believe in a world of goodness and virtue when we allow ourselves to re-enter the imaginative mind of a child, as an adult? Is this a form of regression? Is such a person running away from reality, no different from a lunatic; completely dysfunctional and thus of no use to society?

Next Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).