It is remarkable that mind enters into our awareness of nature on two separate levels. At the highest level, the level of human consciousness, our minds are somehow directly aware of the complicated flow of electrical and chemical patterns in our brains. At the lowest level, the level of single atoms and electrons, the mind of an observer is again involved in the description of events. Between lies the level of molecular biology, where mechanical models are adequate and mind appears to be irrelevant. But I, as a physicist, cannot help suspecting that there is a logical connection between the two ways in which mind appears in my universe. I cannot help thinking that our awareness of our own brains has something to do with the process which we call "observation" in atomic physics.

- Freeman Dyson, 1923 - 2020

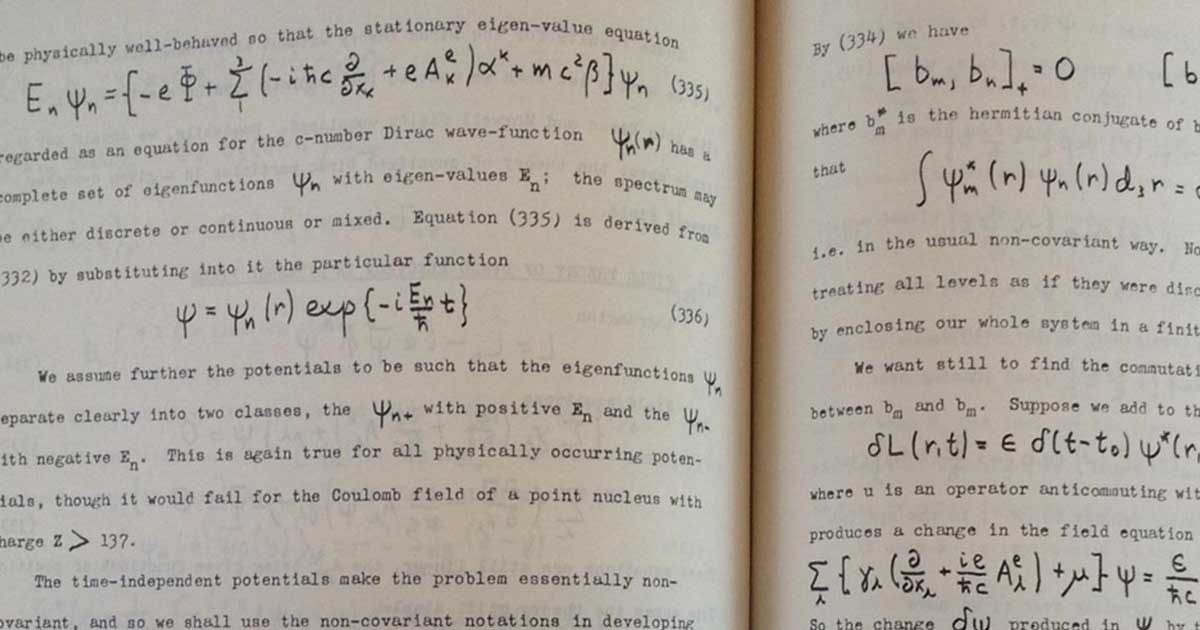

My favorite Dyson story is the one that got him started in his career. Twenty years after quantum mechanics, 40 years after relativity, no one had been able to combine the two in a coherent, unified framework. Then, in 1948, there was an embarrassment of riches. Julian Schwinger, a fireplug who spouted equations as if by direct channel from God, told us it was all about particles and sources.

Richard Feynman, who played the bongo drums and made wisecracks, told us that while we're not looking, the electron does every possible and impossible thing, and he gave us a cartoon system for keeping track of what all those things are.

Dyson was a 24-year-old grad student, and undeterred by their mutually antagonistic personalities, he befriended both of them, channeled both their thought processes, and published a paper in which he demonstrated that the two theories, though they looked so different on paper, always produced the same predictions.

After that, the rigid hierarchical system of academic physics carved a place for him, and allowed him to do whatever he wanted, so that he never again had to take a test or qualify for a degree. He hung out at Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study, home to Einstein, Oppenheimer, von Neumann, and GÃ �del.

He was an original and independent thinker on all subjects. He thought about culture and politics and technology as well as the deep structure of science. He was still writing for the New York Review of Books in his 96th year.

Dyson had a gift for the memorable line and a disarming honesty that admitted the possibility of error. It was, he would say, better to be wrong than to be vague, and much more fun to be contradicted than to be ignored. Dyson was by instinct and reason a pacificist, but he understood the fascination with nuclear weaponry.

- Guardian Obit

Share this:"The more I examine the universe and the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe must in some sense have known we were coming,"

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related This entry was posted in Science by Josh Mitteldorf. Bookmark the permalink.