It's common knowledge that we're all exposed to many different kinds of toxins from the air we breathe, the water we drink, the pesticides and other chemicals we're exposed to and many other sources, and that some of those accumulate and persist in our bodies.

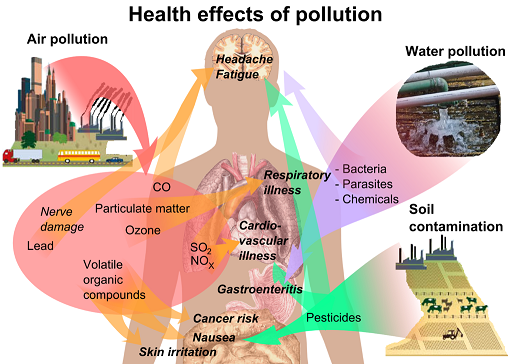

Pollutants have a variety of health impacts

(Image by (From Wikimedia) Mikael Häggström. When using this image in external works, it may be cited as: Häggström, Mikael (2014). 'Medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014'. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.008. ISSN 200, Author: See Source) Details Source DMCA

What we didn't know but researchers have just discovered, is that at least some of those pollutants are not spread randomly through the population, with some individuals having more of one and others having more of a different one. Much like income or wealth, some people have just a little while some have a lot.

A new study of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)--the first that looked at many different kinds of POPs in the same people at the same time--found that that they were strongly clustered, with more than 10% of the U.S. population carrying ten or more different POPs in their blood at concentrations above the 90th percentile. Blacks, people with low incomes, people with a high body mass index (BMI) and older individuals were more likely to carry heavy loads of multiple organic toxins.

When I asked physician and epidemiologist Miquel Porta,

one of the study's authors, about the implications of his findings, he

first cautioned about stirring up fear. "As a physician, I firmly

believe that fear is seldom compatible with a broad vision of health,"

he wrote.

However, he went on to emphasize that

finding that a large number of people have 90th-percentile-or-higher

concentrations of 10 or more known toxins needs to be noted by

researchers and public health authorities:

"Whatever we know, whatever we think we know about the adverse health effects of a given chemical compound, and about the adverse health effects of several different compounds, simply think that it will not be uncommon for them to be--each and all--present at high concentrations in a significant minority of your patients, constituency, citizens, family or friends. And then think about the plausible negative health effects of the combination or 'cocktail' at high and low concentrations."

As reported in the journal PLOS One,

Porta and his colleagues looked at the concentrations of 91 POPs in the

blood of 4739 people living in the U.S. They found that 13% of the

people studied had 10 or more of the most frequently detected organic

pollutants at or above 90th percentile levels. You can view the original

article here.

"Decades after the evidence on the

presence of toxic chemical mixtures in humans became available, official

approaches to assess the risks for human health of such mixtures

continue to lag tragically behind scientific evidence of the adverse

effects of individual compounds and the potential effects of mixtures,"

Porta writes.

"We provide a method to improve exposure assessment. Our method is an important complement to what is usually done."

In other words, it's no longer justifiable to study one toxin at a time in one group of people at a time. Now that we know that many different toxins pile up in certain populations, with the odds tilted by race, age, income and other factors, studies, recommendations and regulations that don't take that into account from the start are likely to seriously underestimate the risks to the health of a significant number of people.

Porta and his colleagues have followed up on these findings by studying the impacts of multiple toxins in seemingly healthy people. You can read my post about that work here.