Republished from The Saker blog

The Story of a Martyr FOR, and not BY, China's Cultural Revolution (2/8)

Actually talk to rural people in China and you can certainly learn of martyrs FOR the Cultural Revolution; talk to disgraced party elites, abusive factory bosses, tyrannical schoolteachers, smug technocrats, pagan witch doctors or parasitic monks, and you get stories of those martyred BY the Cultural Revolution.

Welcome back to the first day of journalism school! "One person's 'terrorist' is another person's 'freedom-fighter'". I am not spouting nonsense such as "all truth is relative", but simply pointing out that perspective shapes opinion (it does not control fact).

The fact is that you have likely never heard a story of a Chinese person who died in order to support their Cultural Revolution (CR).

Nor have you ever heard of the CR's beneficiaries indeed, you likely imagine there were none, except for a power-mad Mao Zedong.

If you have heard anything on the CR and many have not you only heard stories from the CR's victims. The reason for that is: if you are reading this in the West, your media has an informal ban on any pro-socialist story. Anyone who believes that unwritten censorship exists has never worked in the media. (And a pro-socialist story would, after all, empower the leftists in the West and they certainly can't have that.)

The informal ban is separate from, but compounded by, an informal promotion of anti-socialist notions: for example, the 2015 winner for best novel at the Hugo Awards (given to the best in science fiction), was The Three-Body Problem by Chinese author Liu Cixin. The book was even promoted by Barack Obama, and it should be obvious why: the first 25 pages are a rehashing of the same old "the CR was an unholy terror" perspective. Considering the book is about scientists, perhaps such a perspective is somewhat accurate" but China is not full of 1 billion scientists. Democracy means there are losers in policies socialist democracy ensures those losers are the 1%.

(Overall, I found the book to be rather boring "video gamer" escapism, as well as effective (and totally unsubtle) anti-socialist propaganda. Unsurprisingly, Amazon is spending $1 billion on a TV adaptation. For me, the only truly interesting passage described Euler's three body problem in physics and astronomical theory now there was something to meditate upon, finally. My point is: if the book was 400 pages of gamer escapism and 25 pages of pro-CR historical analysis"Obama ain't pluggin' yer book.)

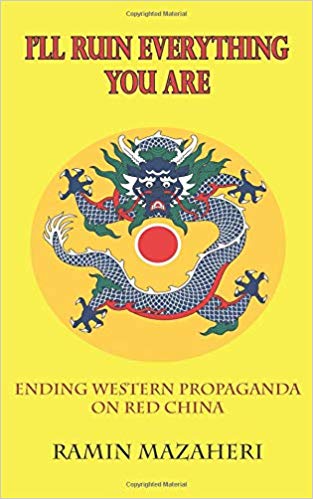

Similarly, no one is plugging Dongping Han's truly revolutionary and eminently readable book, The Unknown Cultural Revolution: Life and Change in a Chinese Village. The key word there is "village" not too many top scientists working there, perhaps, but there are a lot of people who greatly benefitted from the CR decade (1966-76). I gave a brief overview and a few knockout punch data sets in Part 1, and this 8-part series is dedicated to popularizing Han's book and his undeniably confirmed thesis: the CR's educational reform, which became approved following changes to political culture, produced an explosion in rural economic development and rural human capital, and thus China's economic boom actually came before Deng's reforms in 1978. This series is also a roundabout way to popularize my new book, I'll Ruin Everything You Are: Ending Western Propaganda on Red China, to which Han graciously contributed the forward.

Yes, if one was a Chinese science nerd who insisted that they were infinitely smarter than a villager/peasant and thus deserving to rule oppressively in a technocracy" then one likely had a tough time during the CR. This is an old, already told, and often retold story and I am sympathetic but it's time for a new story, for balance and accuracy.

Revolution is bloody, but not as bloody as what leads up to a revolution

Han relates a CR story and an analysis which you have most likely never heard. I will retell it briefly:

Yu Jiushu was a villager in Jimo County (the source of Han's scholarly investigative work, as well as the place of his youth and formative years). During the Great Leap Forward Yu was recruited as a factory worker. The factory failed, causing him to lose his job and forcing his return home. The leaders of his village, during this era of shortage, refused to give him his grain ration on the grounds that he had forgotten his grain ration papers. Yu was forced to share his ration with his mother. Yu's mother committed suicide to avoid the starvation of both her and her son.

The average Westerner would stop right there and say, "Isn't this terrible?" Yes, of course it is.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).