Podcast 5: Understanding Black Suffering with Rev. James Henry Harris: "Interludes" by John Kendall Hawkins

Reverend James Henry Harris is a Distinguished Professor of Homiletics and Pastoral Theology and a research scholar in religion and humanities at the Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology, Virginia Union University. He also serves as chair of the theology faculty and pastor of Second Baptist Church, Richmond, Virginia. He is a former president of the Academy of Homiletics and recipient of the Henry Luce Fellowship in Theology. He is the author of numerous books, including Beyond the Tyranny of the Text and Black Suffering: Silent Pain, Hidden Hope (Fortress Press, 2020). His latest book is N: My Encounter with Racism and the Forbidden Word in an American Classic, a memoir that describes and critically wonders about a graduate English class he took on Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn, and provides crucial insight into the CRT conundrum.

Harris and I conversed by Zoom about his book Black Suffering on August 30, 2022. We discussed his "Interludes." Here is an edited version of that exchange.

This podcast and transcript have been edited for condensation and clarity.

#######

John Hawkins:

Your book, Black Suffering, has three approaches that intersect - academic analysis, sermons, and fiction - and form a synthetic unity of thought about the Black experience. Could you explain the inclusion of "Interludes," your fiction or creative non-fiction pieces?

James Henry Harris:

Thanks, John. The inclusion [of Interludes] comes because of the challenge of the subject matter, and the complexity of it, and how difficult it has been to write about Black suffering in general. In some sense, you know, writing about black suffering smothers the writer, and even the words in a very real sense. So I included fiction because, in some sense, the suffering of Black lives is the stuff of fiction, except that it is real. And so I had to make the work a bit more palatable to get it out of a strict theoretical philosophical framework into a more palatable literary kind of framework. Many of the stories originate in life experience. But the characters, and what's going on, are grounded in fiction, even though a lot of fiction is real life situations.

John Hawkins:

Can you say more about how your fiction complements your academic writing and sermons there? We talked a little bit about it last week, but how do those three merge? How do they work against each other to create movement?

Harris: [00:20:38]

Okay. Well, I'm thinking that one of my interests has always been religion and literature, theology and literature, that kind of thing. And I've tried to meld those two things. And it's a part of my own interest in interdisciplinarity, where I have focused in in recent years on the invocation of various disciplines, not the isolation of disciplines, but how they connect. And I think [that] in a very real sense fiction is a way of making ethical and moral statements about society and about the world. And that's probably the driver of including fiction in this piece. I don't think the book could have been the same, without including some of these pieces, which break up some of the serious discussion and maybe even monotony of discussing Black suffering. The challenge of the subject is extraordinary. I think that there's an interdisciplinary relationship in a lot of subject matter, and that's what I try to employ in this particular piece.

Hawkins: [00:22:46]

Yeah, the interludes worked as a kind of mortar between the bricks of the other structural elements. And I would ask you, is it really fiction or is it more creative nonfiction?

Harris: [00:23:06]

Yeah, that's a good question. It's fictive in many of its elements, but it's creative nonfiction also in some of its elements. For example, let's say "The Prison Visit." I mean, as a part as a part of my work as a minister, I have visited prisons. I have had members of my congregation who have been incarcerated. A lot of black men, in particular, have served time in the prison system. And so it has that realism of experience, but the characters themselves are fictive.

Hawkins: [00:24:01]

I get it. Well, I felt that way as I was reading your story, "America, the Beautiful," too. It seemed fiction up to a point; the first part of it. I read it as a fiction, you know, because it reads like some real place that all of a sudden, wham, sudden events rushing, and you get this merging of past and present immediately. All of a sudden you're like right in the middle of something that's real. Now and, yet, at the same time, history. So this background history sort of comes alive as well, you know, that you weren't expecting. Yet, at the same time, when it does, you know you should have expected it.

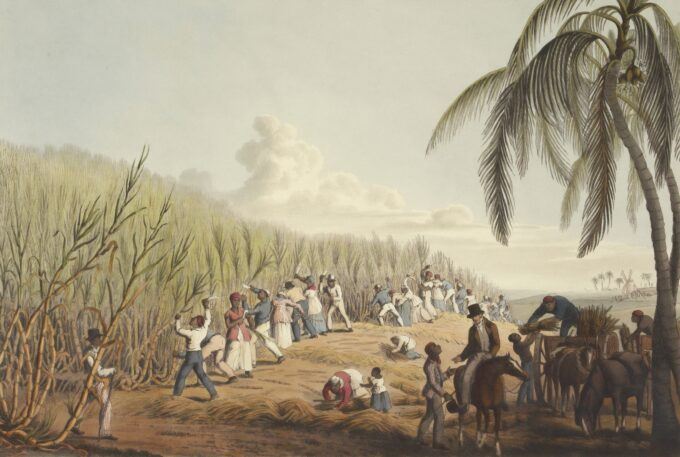

The violence should never have risen, you know, it's irrational, all of a sudden. What's a tense story all of a sudden, then explodes into horror. So. "Plantation" is a story about a man going on a trip from South Carolina to New Orleans. Right. And things start to happen there. They're not quite supernatural, but ominous -- there's a band, then a person in the street bleeding becomes flesh, a trauma flashpoint. Like a horror movie. He visits a plantation and his unpeeling continues. Do you want to talk about the plantation and why the plantation is so powerful as a real and metaphorical force? We've seen the Tarantino film, Django Unchained. Is it like that?

Harris: [00:26:17]

I hated all of those characters in that film and so forth.

Hawkins:

So you didn't see Django as you didn't see him as something like a heroic figure in the line of Nat Turner or something. And I mean, I don't I'm not sure that was written like that. But, you know, Django definitely has that kind of flavor to him. Can you say why you were disappointed in the idea of the film being representational of plantation life?

Harris:

You know, it's very difficult. This is an aside, but it's difficult for me to watch movies like that, and some of the others, because they seem so connected to my own ontology, in my own being. It's almost like I was there. I could really feel like I was almost there in some of those places.

But let me just also say, and I think this gets back to your original point, and that is that there is a creative element in my writing here. And what I have sought to do is to intermingle both creativity and history, and also fiction and nonfiction. And the interplay of those genres, I think, would redound down to the piece being neither fiction nor creative non-fiction in a sense. Hard to pigeonhole or to put in an absolute category. And I think in many ways that's kind of the way life is.

"Plantation" came to me when I was attending a conference on the Society for the Study of Black Religion [in New Orleans]. And part of our conference involved a visit to the Whitney Plantation. All of that is historical. We actually visited the Whitney Plantation. I actually was a part of a conference and so forth. And then from there, you know, I create some characters and just embellish the whole experience. So it's creative activity in that experience. And one of the painful things out of that experience was in actually seeing the cage that slaves were put into. And so, you know, I had pondered whether to call this story "The Cage" or "Prison." I mean, I think either one of those titles would have worked. But that is where the suffering and the pain come in. Because I've noticed that my preoccupation with Black life has been the realization of the extent to which suffering is so ubiquitous.

Hawkins: [00:30:56]

Right. But what is it about "Plantation" that you mentioned? You know, I was wondering, like the Whitney plantation as a museum, as a kind of experience, and people get off their buses and they take tours and all that. Spend money, buy souvenirs. But, you know, there's another place I was looking up online. Have you been to the Lynching Museum in Montgomery?

Harris: [00:33:41]

No, I have not yet. My plan is to go.

Hawkins: [00:33:47]

I read an article about it. And they were interviewing some Black people and some of them were uncomfortable with whites even showing up because [maybe] they feared that there wouldn't be the kind of respect that was required to properly honor the suffering portrayed, and they might ruin the experience for Black people. And it's always there's always the problem of people coming off a tour bus in Montgomery for a rest stop. They don't know what to do with themselves. They have to they go to McDonald's for lunch and they got an hour to kill ad see the Lynching Museum and maybe go, "Huh. I'll check that out."

Harris: [00:34:54]

Yeah. And it's, you know, it's the perpetuation of the capitalist trope. So still making money off of slavery.

Hawkins: [00:35:04] Yeah. Wow.

Harris: [00:35:06]

Visiting that, and really putting what is so deplorable, you know, on display. I don't know if the same thing happens with Auschwitz and other places. I just don't know. But I do know that even when I've gone to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., well, even the smaller museum here in Richmond, you know, these are all extremely painful experiences that I identify with. I guess I identify with suffering on any level, but with Black suffering more particularly. And, you know, and I guess. One of the things that has concerned me is the unwillingness of the majority culture to acknowledge the reality of Black suffering.

Hawkins: [00:36:20]

"Plantation" is a great story, just a fantastic. The characterizations and the events taking place, are really fine. We have these hiccups in history. If we don't get over them, we don't resolve them. Then they just keep coming back to sort of cultural PTSD stuff. Like some VA veteran who gets triggered and all of a sudden he thinks he's in Nam again. Trauma that's unresolved, something anything can trigger; it's just scary like that.

Let's move on to "The Prison Visit." You know, one thinks of the Clintons. I hate the Clintons. And part of the reason is because they were so monstrously destructive to the FDR's system of social relief. The meager safety net that we had for everybody. The attacks on Social Security first started with them. They were ready to give the whole damn thing away. But, you know, one of the expressions that Hillary used was "super predators" to describe Black desperados. Then the whole augmentation of the prison system, the making of prison time, the sentencing itself so onerous and really evil, you know, flat out evil. Poor people who don't have enough money for lawyers and adequate defense are coerced into accepting plea bargains that might put them in jail for five, ten, twenty years for something they might not even have done. And they're being threatened by a lawyer saying, Look, if you fight this, and you force the state to go through with proving beyond a reasonable doubt, they're going to make you pay at sentencing. So you end up the whole idea of Blacks being super predators being, pointed at by these people who've raped the world.

So you have this whole system -- prisons in America being privatized. You know, they're making a profit out of people being in jail. And if you make a profit out of people being in jail, then you want to keep them in jail for as long as possible. So all kinds of things can happen, fistfights can happen that might never have happened. The fights with guards that might never have happened. You know, anything that can lengthen the sentence to someone, you know, it's a total nightmare world. And, you know, it's something that Blacks definitely face more than anybody else. And so I think that's "The Prison Visit" is a really appropriate inclusion in the book. You want to say more about it?

Harris: [00:40:58]

Yes. Well, this is another story that, again, is grounded in some creativity, but also, in some historical fiction to a large extent. It's probably the shortest story included in Black Suffering. Its succinctness and precision is its power of to a large extent. There is so much that people already know, already understand. Prison for black men has become normative in our society. And it's almost like a new form of slavery. And as you indicated, it is now a very capitalistic enterprise, private prisons, all of that designed to make money off of Black suffering in a very real sense. And that's one of the things that's troubling to me as well. This story is, to some extent, grounded in my own experience in visiting prisons. It would be very difficult to make up the experience of being there -- the people at the desk, the tough, gruff Black woman that, you know, told me to go back outside or told the character 'me' to go back outside and leave everything outside, leave the phone, leave all of this stuff outside. I mean, none of that is fiction. It's all real, except that the character, the characters have been fictionalized. And then I have the narrator who is a smart, eloquent person, you know. But in that particular story, the prison guard was not feeling any of what the narrator was saying. Because the narrator was trying to make her see that she was in prison, too. Everybody behind those walls was in prison to some extent.

Hawkins: [00:43:37]

Yeah.

Harris: [00:43:39]

So, you know, when I was writing the story, I was really thinking of Kafka to some extent in his story as well.

Hawkins: [00:43:51]

What, "In the Penal Colony?"

Harris: [00:43:54]

Exactly.

Hawkins: [00:44:24]

Can you just talk about "Powell Street Station"? How is that different than "Plantation" or "The Prison Visit" in terms of its approach? And what were you trying to accomplish with that particular story in the collection?

Harris: [00:44:37]

I was trying to [relay] the complexity of life in San Francisco -- and also the kind of dialectic that is so evident in urban life, where you see glitter and posh next door to abject poverty and homelessness, and all kinds of other things. So, I was trying to draw that contrast in "Powell Street Station," and also trying to show the narrator's disinterest in public transportation, and other kinds of things. And some of the characters in that story are also grounded in my own experience. And I was actually at Powell Street Station, in fact, to attend my son's graduation from UC Berkeley. And that was the impetus for the development of the story.

Hawkins: [00:47:14]

But what's the story about?

Harris: [00:47:19]

The story is about the place itself. The place is a key character in the story. And the story was originally named "Confusion of Horizons" or something like that. The plot was about how things fuse. At that BART station. And there's a lot of fusion culture that's going on in San Francisco itself. It was a fusion of horizons, then confusion of horizons, and then I thought I'd just go straight with "Powell Street Station," which I thought would be easier for people to identify with.

And so, I think if I was talk about plot, it's all about how things fuse, and the coming together of so many different people, so many different cultures. You see people in businesslike attire. Folks who are very ragged and tattered. Some people talking to themselves. Other people on their laptops, trying to make deals and all kinds of other things. And so it was, in my view, representative of a culture, a fusion of cultures, but also the whole issue of public transportation as well.

Hawkins: [00:49:25]

Right. One of the things about that title is it sounds like it would be a nice title for a jazz tune, you know, like "The Powell Street Station Stomp" or something, you know? And it's got that feel, you get with Scott Joplin writing a rag for it or something like that. This sort of jaunty movement that all of these musical figures coming in and like you say, fusing, you know, it's kind of really busy kind of thing to it, vibe to it.

But those are good stories. The Interludes come across as mortar that sort of keeps the bricks together of your academic concerns and sermons. It's definitely lyrical. You do a nice job painting people and their situation. So imagistic. Even poetical at times. But speaking of poetry, you said you weren't going to read poetry at the end of this week's session. You want to do something a little bit different. What do you have in mind?

Harris: [00:51:08]

I thought this bit fits in very nicely to what we've been talking about today, because it is grounded in narrative theory and in life writing. And I think in some sense a lot of my work could be categorized as life writing. Just a few musings that I have written down for the day:

I find myself wandering around campus, looking into classrooms, trying to overhear what the teacher is saying. What's being expressed to the new group of students. There is something addictive about school to me. I love it regardless of my status. I like being a student just as much as I like teaching. It could be a seminar in Schleiermacher, the German philosopher and theologian. Or it could be a course on narrative theory. A course in ethics or a course in life writing. So I need to take another course. Not necessarily. My colleagues and the dean at our little school are always making snide remarks about me. He's always in school. Haven't you been in school long enough? I found this to be very interesting, especially since all of my colleagues are academics or academicians. Most of them seem to hate school and hate scholarship. They have no love for the life of inquiry, the life of questioning, the life of writing. And yet, they want us to believe that they are professors of some obscure discipline. A discipline that apparently has not changed since the invention of the printing press. I recognize that I'm a digital immigrant, a neophyte in so many disciplines, so I struggle to stay involved in studying and reading and writing and dialogue with the great works. I prayed to the muse, the daughters of Zeus, that my strength will remain in my body and in my mind. I pray that the voices of my soul remain fresh and vibrant, so that every day I may sing a new song, write a new poem, and rejoice in the goodness of God. My story is not a straight line, not linear, but circular and zig zag. It does not go from A to B, but from A to G or even from B to A. It's a strange logic that engulfs my experience. It might be my spirit, my restless spirits. It might be my hopes. It might be my dreams.

Hawkins:

Thanks. Talk with you next week.

#####

James Henry Harris's books N (2021) and Black Suffering (2020) can be purchased at Fortress Press.