Introductory presentations of ranked-choice voting (IRV) usually begin with a description of how magically it corrects for the spoiler effect. The example is a three-candidate race with two of the candidates so similar that they are difficult for voters to distinguish. These two candidates are supported equally by 60% of the voters.

Since plurality voting makes no accommodation for sharing support, voters must choose just one of the two very similar candidates and as a result, each of these two candidates are apt to get only 30% of the vote. This causes the third candidate to win the plurality election with 40% of the vote, despite the fact that sixty percent of the voters would have preferred either of the other two candidates.

Rather than avoiding the vote splitting. IRV corrects for it using multiple rounds of ballot counting. In effect, the 30% of the votes that lose the first round have their votes transferred to the other of the two candidates for the subsequent and final round. While that may seem like a neat trick, the multiple rounds of vote counting introduce intricacies that complicate elections and introduce other problems.

We cannot even conclude from this one example that the spoiler effect is entirely eliminated by using IRV. In an earlier article of this series, we introduced an example of a spoiled IRV election with five candidates; but we might still wonder whether at least IRV avoids the spoiler effect when there are only three, and perhaps even four candidates.

The spoiler effect seems to never be clearly spelled out, but it would seem to be an election failure that stems from vote-splitting. In the example plurality election, the two similar candidates split the votes that could easily have gone to either one. But we might notice that in an IRV election there remains the problem that two similar candidates, A and B, will split in the sense that half of their (combined) voters will rank them in order as A, B while the other half will rank them as B, A. That appears to be an alternative way for the spoiler effect to resurface. Might we find an example of an election with a clearly anomalous outcome resulting from this more subtle sort of vote splitting?

Consider the example election illustrated in Figure 1; 49,000 of the 100,000 voters prefer either A or B equally and this is a greater number than the 38,935 voters who prefer candidate C. There is a handful of 12,065 other voters who have slightly different preferences, but even these 4,585 voters list either A or B as their first choice, but it seems apparent that most of these voters harbor some animosity toward candidate B. In any event, it should be clear that the rightful winner of the election should probably be A, but surely either A or B. It is the iterative counting of ballots with IRV that allows these other voters to play an outsized role in the election outcome.

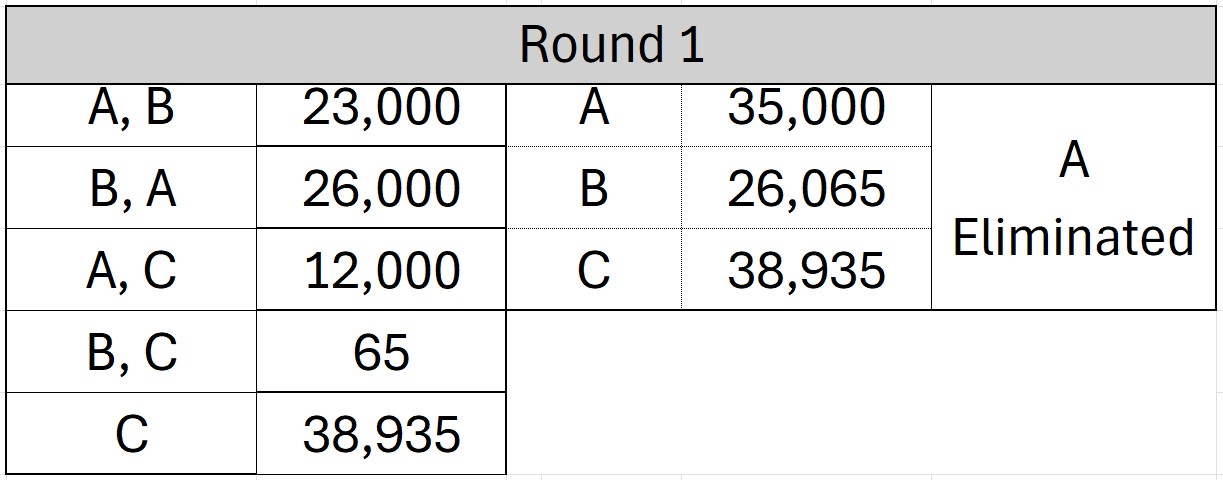

Figure 2a. First Round of IRV Tally

(Image by Paul Cohen, screen capture from Excel Document) Details DMCA

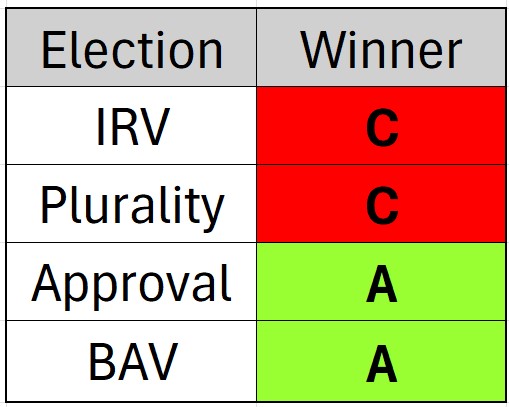

In the first round of the IRV tally, A is eliminated and as shown in Figure 2b, C is the winner using ranked-choice voting. Not surprisingly, Figure 3 shows that vote-splitting produces the same outcome in a plurality election. And jumping ahead to Figure 6 we see that plurality voting also suffers from that spoilage whereas approval voting and its close cousin, balanced approval voting, manage to avoid this particular example of the spoiler effect. Both of these systems simply avoid the vote splitting in the first place, rather than attempting to correct for it afterwards as IRV tries to do.

Figure 4 shows the details of the approval vote-count and Figure 5 illustrates this for BAV. It is true that details of voting for BAV in particular could be disputed. but I tried to make reasonable judgements in this regard. It seems impossible to confidently predict how voters might react, even to a change in the weather, much less a change in the voting system.

Figure 6, Summary of Election Results

(Image by Paul Cohen, screen capture from Excel Document) Details DMCA

What we have demonstrated with this example election is only that ranked-choice voting fails to eliminate the spoiler effect, even for elections with just three candidates. It is dangerous to generalize from one example, or even from several examples, to claim much more. This danger is demonstrated here by the apparently widespread belief that, because ranked-choice voting manages to dodge one style of spoiler effect, then surely it avoids all spoiler effects. It would be as much of a mistake to conclude from this single election example that approval voting will always be as reliable a voting system as is BAV. An example of how wrong this conclusion would be can be found in an earlier article in this series.

There is much to be said in favor of BAV that cannot be said of the other systems discussed here. In the presence of a duopoly, BAV voters from each of the two dominant parties cancel the votes of the other, making a win by a third party a serious possibility; we might say that with BAV in use, a duopoly is an unstable situation, apt to be short in duration. With some confidence we can conclude that BAV will undermine any duopoly and the bitter polarization that the duopoly can create. Also, BAV avoids favoring candidates simply because they are famous, just as it avoids favoring candidates who are scarcely known. And BAV allows voters to freely express their opinions about each and every candidate without punishing candidates for abstentions and without forcing them to gamble regarding electability.