So. I suppose that what one could do is wonder whether these statements are simply a smoke-screen for some nefarious, underhanded deals going on. But not only do I not have the faintest clue whether that's the case or not, and see no good reason for throwing uneducated guesses around, author Ugo Bardi put it even better when he said that "we tend to interpret the present downward cycle as the result of strategic choices or conspiracies, but this is mostly an illusion (the illusion of control)." That being said, what I do see as being important (and useful) is looking at why prices started to get so low in the first place.

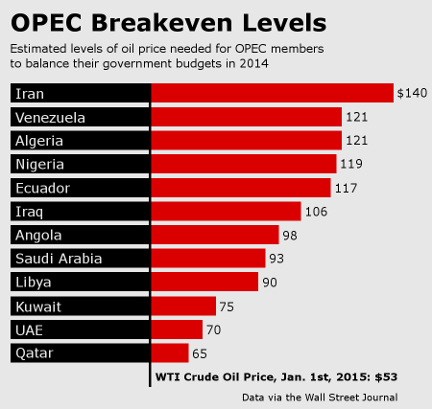

Estimated oil price levels needed for OPEC members to balance their government budgets in 2014

(Image by Allan Stromfeldt Christensen) Details DMCA

First off, certain OPEC members -- namely Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar -- have either built up such substantial financial reserves and/or can extract oil so cheaply that they are able to bear the brunt of low oil prices for some time. Not so much others.

While Iran needs oil in the $100+ range in order to balance its books, Venezuela is in the worst position of all. While the Latin American country is already a very polarized nation, oil accounts for 95% of its export revenue. Low oil prices could therefore easily make a grim situation worse, some people having a propensity to become hostile when their standards of living continually depreciate. Likewise, a default on Venezuela's debt wouldn't be out of the blue.

But perhaps more pertinent and interesting is: what of the non-OPEC producing countries? This, I think, would be a much better area to look at, seeing how it would shed much light on how we got into this situation in the first place.

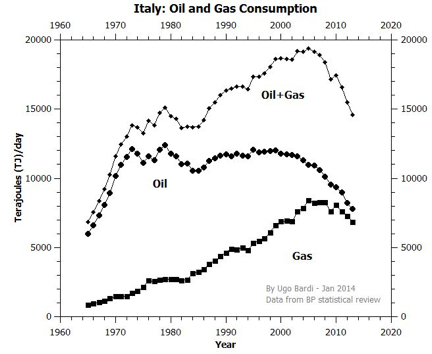

First off, it's worth noting that for the past three years or so, before oil's recent crash, the price of crude has been bouncing around the $100 mark. This was a relatively expensive range, particularly in comparison to its long-standing rate of $20-$40 per barrel for more than a decade, before its gradual then meteoric rise to $147 in 2008.

Since oil is entwined with the price of pretty much everything nowadays, its changes in price can have a significant effect on economies (as we currently [mis]understand the term). With higher and higher oil prices sapping a greater percentage from expenditures -- be it of "consumers" or businesses -- a price point is eventually reached where goods become so expensive that those who can't afford them anymore simply stop buying them. This is what is called "demand destruction."

When demand dries up and fewer goods thus end up being bought and sold, a glut in oil supply results, which ends up crashing prices. This is simple supply and demand. Along with other factors, this is what happened after the $147 oil price spike in July of 2008, and resulted in oil tumbling down to $32 by December of that same year.

While the ensuing low oil prices get seen by some as a boon (via the expectation that consumers will have more money to spend), the opposite problem actually kicks in -- namely, "offer destruction." Since many businesses get forced to close down due to crashing oil demand and so in effect get fewer sales, and since a significant number of people get their hours cut or even lose their jobs, there often-times isn't enough money to pay for oil and other goods, regardless of how low the prices go. This is what happened in 2009, referred to as the Great Recession.

To return to the first paragraph of this post, this is where I got thrown off. To digress:

As mentioned earlier, 2005 is seen by some as the year that conventional supplies of oil peaked. It is because of this (and a few other factors, like speculation) that oil climbed to $147. Although prices subsequently crashed due to demand destruction, they eventually made their way back up, to the point that several unconventional forms of oil (shale oil/fracking, tar sands, and deepwater offshore oil) became somewhat profitable.

The problem with peak oil is that when (if?) growth kicks in again, and since more and more energy is getting used, soon enough the increasing levels of energy-use may very well butt up against maximum extraction levels, resulting in a shortage in supply and causing the whole demand and offer destruction cycle to kick back in again.

Furthermore, and as far as one theory goes, higher highs and higher lows will occur. That is, instead of maxing out at $147 per barrel, oil will reach, say, $200 per barrel, before crashing down to $80 or so instead of $32. And so forth.

And it is because of this notion that peak oil pulled a fast one on me. Expecting the higher high having to happen, what I didn't clue into was that oil prices at a high enough level for a prolonged period of time would be enough to have a similar effect as a quick rise to $147.

Case in point, one can look at countries that have recently slipped into recession or simply haven't gotten out since 2009 -- Greece, Spain, Italy, Brazil, and so forth. Furthermore, some of the more robust and rich countries are seeing their growth wane -- Japan, China, Germany, to name just a few. For what is a slowdown in Europe leads to fewer consumer purchases from China leads to less iron ore and coal bought from Australia.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).