In the previous article in this series, I made an inaccurate and overly broad claim that:

Should the (Condorcet) pairwise, votes be derived from a ranked list, that defect infects the derived Condorcet ballot so that it also favors the most widely known candidates.

The defect in deriving the pairwise preferences needed for Condorcet scoring lies in the treatment of candidates who are left unspecified on a ranked-choice ballot. The unstated qualification was that the pairwise votes for the Condorcet contest would first be filled in with a default position in the list at the very bottom. However, even with that assumption, preferences between the unlisted candidates would remain undetermined whenever more than a single is left off of the ranked list. But there remains the alternative of interpreting the ranked ballot literally and simply allow many pairs to remain unspecified when appropriate.

An example shows the significance of insisting every pair to be resolved with a preference indicated for candidate and that is the widely familiar example of an election has two very similar candidates and there is a third with less support. This is the example that serves to illustrate the spoiler effect for plurality voting. Specifically, 60% of the voters prefer either of the similar candidates and only 40% prefer the remaining candidate. But in a plurality election, the two similar candidates split the 60% to get 30% each and so lose to the third candidate with 40% of the votes. This example shows why plurality voting is considered an inadequate system for voting whenever there are more than two candidates. With only two candidates plurality voting works as well as any other voting system and it is simpler than most alternatives.

But let us now consider the same election scenario, but using Condorcet scoring. For this illustration, let us assume there are 1000 voters with 600 of them preferring candidate A or B about equally and another 400 clearly preferring candidate C. The election of C using plurality voting is what characterizes the spoiler problem for plurality voting, but we will see that C is also elected in a realistic application Condorcet scoring.

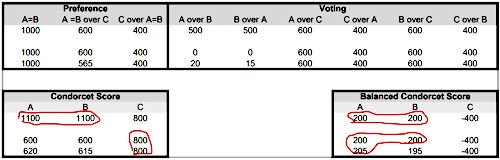

How voters feel about the candidates is described in the upper left chart below, and the pairwise interpretations of those preferences as votes appear in the upper right box. From that upper right box it is an easy matter to compute the Condorcet scores (lower left box) and the balanced Condorcet scores (lower right box). Circled in red are the winners for each of these two voting systems and you can see that in two of the three cases, C is the winner, illustrating the spoiler effect with Condorcet voting.

The case illustrated by the first row of each table assumes that all voters provide a preference between each pair of candidates. As difficult this is to imagine this actually happening with 1000 voters, there is the possibility of eliminating the other ballots as being spoiled. This might entail throwing out the vast majority of ballots, however, and it probably would not be well received by voters.

The second and third rows illustrate the more realistic situations. In those two rows, Voting box (upper right) shows how the vote would be when voters have the option of skipping over pairs of candidates when they judge no preference between them. The middle row does make the unlikely assumption that none of the voters who prefer A and B have any preference between the two. But personal or family relationships may lead to a preference and the third row illustrates that possibility.

The Condorcet winner, as shown in the last two rows, is no more satisfactory than would expect with plurality voting; both rows illustrate the spoiler effect. Balanced Condorcet results do not exhibit this defect, however.

This should not be understood as a recommendation that balanced Condorcet voting should be adopted for our elections. Balanced approval voting (BAV) seems a much better option for actual elections, if only on the basis of its greater simplicity. As a bonus, BAV promises to encourage more political parties to be established as viable competitors; this is of critical importance because as noted before, when voters are provided only two options, no alternative voting system could improve significantly over plurality voting.

These observations raise the question of what criteria would be best for choosing among different voting methods. My impression is that most people first consider their personal impact; how they would feel about voting if using a particular voting system. They might ponder how difficult it would be to decide how to vote and how confusing the actual voting would be. Given some time to reflect, some might also consider to how easily and thoroughly it would allow one to accurately and fully express one's opinion. Only much later, on deep consideration, might voters consider how accurately these expressions would in fact be interpreted and whether democracy would be enhanced or weakened. None of these are particularly easy questions but a shortcut would be to at least avoid systems that, like plurality voting, ranked-choice voting or Condorcet voting which we can demonstrate as instrumental in clearly faulty elections.

An approach for comparing different voting systems should begin with comparing the ballots and to consider what information is gathered. It is sometimes possible to predict from using one ballot design, A, what the voting would be for a different design, B, and we might conclude when this is possible that design A provides more information than design B. From this standpoint we might say that a ranked voting ballot is more expressive than than the Condorcet ballot. The more expressive ballot in this regard should be expected to make voting more difficult, in return for providing more insight into voter opinion.

But such conclusions should be tempered by a consideration of how accurately the voting using design B are predicted from the corresponding design A ballot. It is also very important whether the extra information gathered with design B is used effectively by the voting system and in the end, how accurately all of that reflects actual voter opinion. These are important but difficult questions that only grow more difficult with increasing complexity of voting systems. It seems best to keep things simple by adopting approaches which collect accurate information from voters in a clear, simple and effective manner. The goal should be to accurately gather voters' sentiments and take those sentiments accurately into account; this requires voters to be asked questions they can easily answer truthfully.

Approval voting (AV) and balanced approval voting (BAV) can be compared in the manner described above since from a BAV ballot you can readily predict how a voter would fill out an AV ballot from that voters BAV ballot (by just ignoring all of the votes of opposition). But would this be an accurate prediction? Not likely it seems because many AV voters, lacking a way to cast explicit votes in opposition will (untruthfully) vote to support additional candidates because they hope to ensure the defeat of some particularly despised candidate; voters often have strong feelings of opposition to particular candidates. Such an untruthful vote does not actually reflect a favorable voter sentiment about that candidates, though it is likely that would be how the vote would be interpreted. Voters, lacking a better way to express opposition, resort to a deception and in turn that corrupts the information that is gathered through the ballots. Consequently, from the ballots alone, it becomes impossible to deduce the true preferences of the voters.

BAV adopts the view that voters may find several candidates suitable for office and other candidates unacceptable; and it also allows for the possibility that a voter may be undecided or uninformed about yet other candidates. BAV seeks to determine into which of these three categories a voter would place each candidate and it chooses as the winner the candidate who would disappoint the fewest voters while pleasing as many as possible. It is hard to think of why a voter would lie about such simple questions. AV does take much the same approach as BAV, but (unfortunately) with the added assumption that opposition is best ignored; votes other than for approval are simply ignored in tallying an AV election (a qualification here is that Latvia uses BAV and it does take into account these other votes, but only for the purpose of avoiding negative tallies).

In even greater contrast, plurality voting seems to take a very ridged view of voter opinion, assuming in effect that voters are completely committed to one and only one candidate. The plurality ballot simply asks each voter which candidate that is, but that is a difficult question when the underlying assumption is false for a particular voter. Ranked voting relaxes this a bit by assuming that each and every voter surely has a first choice but if that fails then also a second choice and so on but even that weaker assumption is unlikely to be the case for all voters. Neither these systems nor Condorcet voting contemplate the possibility of a voter being open to compromise, willing to be quite satisfied with electing any of several of the candidates. Aside from BAV, none of these systems bother to allow such a voter to describe which candidates the voter finds unacceptable; instead these systems insist that the voter invent preferences that really are not true.

Aside from AV and BAV, these systems require voters to express, in one way or another, preferences between different candidates. These voting systems make no effort to distinguish whether a voter finds a particular candidates acceptable, perhaps assuming this never happens. Suppose a voter indicates favoring candidate A over candidate B; it is possible that the voter feels A is acceptable and B unacceptable, but it is just as possible that the voter finds both A and B acceptable or both unacceptable. This leaves these systems in a poor position for determining which candidate is felt to be most widely acceptable by the voters. The elected candidate could even be one that a majority of voters find to be unacceptable.